The Blood of Elves – What Came Before the timeline of The Witcher? | Part 2 of 'History and Fantasy'

The Conjunction of Spheres is the true catastrophe that trapped elves and fantastic beings in The Witcher's historical time where one race consumes others. In Myth though, they remain neither dead nor alive, and Elder Blood preserves this power of moving freely between Myth and History.

Vorgeschichte of the Elves

Think of Mythic Time and Historical Time as of two distinct ontological modes of being in The Witcher, and note that it is Mythic Time from which everything flows and in which everything is preserved. In the beginning, in Mythic Time, there is the archetypal template that, despite being subject to repeat euhemerization in our meta fantasy, is worth imitating and recovering by ‘re-entering’ it. But how? What kind of consciousness can move between these registers? Why, the kind that is able ‘to tear apart the rigid corset called rational cognition’ that restricts modernist-rationalist thinking.

It is for a reason Elder Blood is the Blood of Elves – elves who, for Tolkien, were the quintessence of Faërie. Fairy Tale and myth. Allegedly too, the title ‘The Witcher’ was given by the publisher out of marketing considerations, while Sapkowski had intended to call the pentateuch ‘Krew elfów’, Blood of Elves (with the first volume ‘Lwiatko’, or The Lion Cub).[1]

‘The legacy of remarkable blood is concentrated in [Ciri]. Hen Ichaer, the Elder Blood. Genetic material determining the carrier’s uncommon abilities. Determining the great role she will play. That she must play.’

‘Because that is what elven legends, myths and prophecies demand?’ Sabrina Glevissig asked with a sneer. ‘Since the very beginning, this whole matter has smacked of fairy-tales and fantasies! Now I have no doubts. My dear ladies, I suggest we discuss something important, rational and real for a change.’

‘I bow before sober rationality; the power and source of your race’s great superiority,’ Ida Emean said, smiling faintly. ‘Nonetheless, here, in the company of individuals capable of using a power which does not always lend itself to rational analysis or explanations, it seems somewhat improper to disregard the elves’ prophecies. Neither our race nor our power draws its strength from rationality. In spite of that it has endured for tens of thousands of years.’

—Baptism of Fire

As a culture, elves show pre-rational modes of being and thinking. Through their ecologism, (near) immortality, and presence ‘before other things,’ they traditionally embody the cyclical perspective in Fantasy. It is possible their wisest may grasp what this means for their race in terms of The Witcher’s story structure, which is textually supported by the way Auberon and Avallac’h talk about destiny, eternity, and Ciri’s role[[History and Fantasy. Or 'how to talk about time travel in The Witcher.' Part 4|]] in it. For elves, who adjust their lives according to the recurrence of seasons, there is nothing unreal in divining the fate of worlds and characters as if it was a plot in the book of books; narratives recur with the same cyclicality as nature, and this pattern holds power in itself. (Know your classics!) It would seem then that what for Sabrina is an epistemic divide is, in fact, an ontological difference for Ida. In their cultural practices and relation to time, elves exist as the mythic consciousness incarnate. They can be thought of as of a story-bound, inherently magical and fantastic race. As anti-historical from human perspective, call them Eliade’s ‘archaic man.’

Indeed, Sabrina’s lamenting the humbug of fairy tales and fantasies is strikingly ironic because doing magic, in essence, lies in two simple words: I wish. I will a thing to be X rather than Y. A profoundly unreal practice of affecting the material reality, no? Yet this is, more or less, how magic and imagination work. Elves may have taught humans magic but they work magic differently than humans (for example, they don’t need to utter incantations), and nature itself responds to them without the need for ‘extraction.’ ’The sun shines differently, the air is different, water is not as it used to be. The things we used to eat, made use of, are dying, diminishing, deteriorating. To you, the earth pays a bloody tribute. It bestowed gifts on us. For us, the earth gave birth and blossomed because it loved us.’[2]

Something in the nature of reality changed after The Conjunction of the Spheres and it cut the elves off from their natural way of being. Based on Sabrina’s and Ida’s exchange, and considering the story of human history of magic in the Gallery of Glory, we could assume that by introducing humanity into the original Mythic Time of Fantasy, Sapkowski imposed a rational frame on fairy tale. Just as human mages see doing magic as a scientific practice of harnessing and taming the power of the elements, humanity sees everything else too. Humanity’s very presence in Fantasy cannot be anything but colonial and demythologizing because in one way or another, they are the modern reader’s way in. Primordial magic is intuitive, requiring only that one hardest of skills: knowing what to wish for. Knowing what to dream, to make, to bring forth where at first there was only a need. It matters a lot, for example, in guiding Ciri’s movements between places and times, i.e. possible (states of) worlds, because she is deploying that very same magic that is inherent to the elves.

No one could tell how long it lasted, because it was unreal.

Like a dream.

—Lady of the Lake

Mythic consciousness, like the Mythic Time, is atemporal, applying to dreams, fairy tales, the Unconscious. Time means nothing in a dream. Past, present, future are but the happening moment. Only when the dream is written down does it obtain a fixed shape, a causal chain and a character; we entrap the mythical unicorn in the garden of our encyclopaedias.

A cognitive shift took place when oral traditions were bound in the written word. Words, uttered and embodied, lost their magical power as events, acts of imagination that returned and recurred eternally as moments that you could enter. By contrast, the written text is static, proceeding linearly, besieged by the demand of consistency and coherence in its structure. There are tricks for making it more complicated, but that is one of its main constraints. The Alder King cannot be simultaneously 600 and 1500+ years old – the laws of time dilation must apply! Auberon not Oberon – name is just a referent not essence! Pre-rational thought, by contrast, involves fluid, living mythology; a constant grasping of infinite possibility. Both/and not either/or. To write down any story means to fix that story in a time; the author, the magician sub-creator, binds his creation with the written Word. When the imagined element is put down, it dies, losing its ability to continue growing and shapeshifting at least within the confines of that tale. The Elder Races ‘fade’ in history; that is, they are – non-euphemistically and historically – killed off.

Before Andrzej Sapkowski began his act of binding, there were only spiralling mists and dreams. Honouring storytelling’s cyclicality, the author inserts the cyclical nature of time to the very genesis of his Never-Neverland. The catastrophe that sets the stage of the world in The Witcher is a migration that happens over and over again. Each time a new culture arrives, the tribe who receives them enters a time of upheaval and change which leads to a sense of a loss of paradise that existed before the entry of Other, different minds into their lives.

...a drama acted out by the Ancestors of men and by Supernatural Beings different in type from the all-powerful, immortal Creator Gods. These Divine Beings are subject to changes in modality; they 'die' and become something else, but this 'death' is not an annihilation, they do not perish once and for all, but survive in their creations. Nor is this all. For their death at the hands of the mythical Ancestors changed not only their mode of being but the mode of being of mankind. From the time of the primordial murder an indissoluble relation arose between Divine Beings of the dema type and men. Between them at present there is a sort of 'communion': man feeds on the God and, when he dies, joins him again in the realm of the dead.

—Mircea Eliade, Myth and Reality

Nevertheless, in mythic consciousness no end is seen as final. Elves do not vanish without a trace, they become, for example, the Wild Hunt – existing in an altered modality as humans ‘inherit’ elven lands and language, consuming their civilization. ‘It was the end of one… race, followed by the appearance of another’ (Eliade, p. 54). They are neither dead nor alive in Myth. Euhemerized, these are the elves who ‘left for a more interesting reality.’ But as migration forms the Ur-Myth of this storyworld, nothing new happens without being a repetition of the archetypal pattern. Elves are what humans will one day become when they are in turn displaced, mythologized, and transformed into the next iteration of fairy tales. They will ‘go away’ in one form to survive in another. History’s progression (to the end of the Plot) inevitably ends in an act of blending into the substrate of all Fantasy.

In the mythic consciousness that Bolesław Leśmian called the realm where fairy tale unfolds itself endlessly ‘in order never to reach an end’, demise is merely a switch between planes of being, passage into timelessness rather than final annihilation. Reality exists perpetually in states of becoming, and ‘the end’ is only a journey through the looking glass into into imagination’s infinite recursion. In The Witcher storyworld then, we might view the act of taking an archetypal form of the Wild Hunt as the elves’ attempt at re-mythizing themselves; a half-way restoration of their pre-Conjunction way of being. Harbingers of upheaval and change, from the past into the past, they are, in a sense, already dead while looking for restoration and renewal in a new turn of the wheel of the Universe.

Such is Sapkowski’s template for history more broadly: with fire and sword through fire and blood. Freedom to make history is illusory for nearly everyone. Romantics like Aelirenn perish. Pragmatists capitulate to the winners and quietly accept historical horrors along with subhuman existence, or choose exile. Others seek means for a flight – a mass flight – into a new beginning. Ithlinne’s prophecy – that famous poetic mockery of rational worldview – turns out to be an instructive metaphysical artefact, describing the elves’ desire to find a way back into the beginning. Because in fabled beginnings there are no bounds to possibility.

‘I want it,’ Avallac’h continued, stopping and indicating with a hand, ‘to survive. Even when we depart, when this whole continent and this whole world ends up under a mile-thick layer of ice and snow, Tir ná Béa Arainne will endure. We shall leave this place, but one day we shall return. We elves. We are promised this by Aen Ithlinnespeath, the Ithlinne Aegli aep Aevenien prophecy.’

—The Tower of the Swallow

In any good fantasy there must always be elves or elf-like entities. It’s a classic!

‘And so shall begin the extinction of the world. Do your recall Ithlinne’s text, Witcher? Who is far shall die at once; who is near shall fall from the sword; who hides shall die of hunger, who survives shall perish from the frost… For Tedd Deireadh, the Time of the End, the Time of the Sword and the Battle Axe, the Time of Contempt, the Time of the White Cold and the Wolfish Snowstorm shall come…’

‘Poetry.’

‘Do you prefer it less poetic? As a result of a change in the angle of the sun’s rays, the margin of permafrost will shift–significantly. Then the mountains will be crushed and pushed back southwards by the ice sliding from the North. Everything will be buried under snow. Under a thick layer more than a mile deep. And it will become very–very–cold.’

—The Tower of the Swallow

Famously, Sapkowski has claimed that a book is just a gathering of letters (ink on a page is what Geralt truly looks like) and when the legend runs its course, the letters, like stick figurines, are buried by the blank white page: ‘people calling for help. At the bottom, deep beneath the ice … is a frozen world.’[3] Until the thaw of a new spring. Until the beginning of a new tale.

‘As far as we elves are concerned, Ithlinne is more explicit: only those who follow the Swallow will survive. The Swallow, the symbol of spring, is the saviour, the one who will open the Forbidden Door, signal the way of salvation. And make possible the world’s rebirth. The Swallow, the Child of the Elder Blood.’

—The Tower of the Swallow

Read poetically or scientifically, as a sacred text or a profane forecast, Ithlinne's prophecy conveys the same truth: Myth’s openness returns when the Story ends. Creation and destruction succeed one another ad infinitum in the cyclical time doctrine that sits at the heart of the The Witcher’s events. Elves, classically, refuse history, because its hallmarks are meaningless suffering and demise, while elves are natural embalmers. Fantasy authors usually relent and eventually yield to Myth its due, letting Faërie re-submerge into its origins in the mists, in our – a fantasizing species’ – consciousness. And sometimes they also ascend a human soul into the eternally plodding Pot as a statement.

Sapkowski leaves his elves’, and Ciri’s, fate in his Never-Neverland implicit and appropriately so. Legendary matter exists always in a state of incompletion. One story ends, another begins. Fairy tale is a way of being. In The Witcher, it is Geralt’s story with Ciri that ends, but elves and unicorns, and Ciri, remain part of the Mythic framing, which continues and reappears eternally.

‘An elven mandala… The so-called blathan caerme, or garland of destiny: stylised oak blossom, bridewort and broom flowers. A tower being struck by lightning–a symbol of chaos and destruction, for the Old Races… And above the tower–’

‘A swallow,’ Ciri completed. ‘Zireael. My name.’

[…]

‘Come here, girl with a collar on her neck. Examine the marks etched into the blade. You don’t understand them, naturally. But I shall explain them to you. Look. The line delineated by destiny is winding, but leads to this tower. Towards annihilation, towards the destruction of established values, of the established order. But there, above the tower, do you see? A swallow. The symbol of hope.’

—The Tower of the Swallow

By entering the tower, a symbol and allegory of a rite of passage in Tarot, an initiation journey begins for Ciri. She takes the right path beyond the profane, frozen world that birthed her and has tried to claim her with shackles and a collar. Little does she realize, however, that mythic existence forms its own noose with which it claims a character and dissolves their identity among archetypal forms and functions.

‘Each new spring,’ writes Eliade, is ‘the same eternal spring (that is, the repetition of Creation).’ The Swallow, a girl with a collar on her neck, a tor’ch of destiny, can deliver the elves to a new beginning by re-starting their world. With Elder Blood, elven identity as legendary manifests in the way Ciri can exist in various times and places simultaneously. In human terms it is down to ‘genes’; or in our terms, an ontological inheritance. Ciri’s origins are in fairy tale. Except unlike for the elves, to whom the prophecy is consoling, she is attached to history, to humanity’s mode of being in which there is only one Geralt and only one Yennefer.

For the elves, Eternity must prevail over history. ‘The man of the traditional cultures refuses history through the periodic abolition of the Creation, thus living over and over again in the atemporal instant of the beginnings,’ writes Eliade. In order not to perish in The Witcher’s strand of Historic Time, elves have to go and be elsewhere for a bit. It is the mythic pattern that accompanies these beings in all of Fantasy Literature – they leave and sail into the West. The storyworld and their nature will be renewed eventually. But for the Swallow, this prophetic mythical existence feels like a chain, the meaning of which becomes clear to her only after her story has seemingly completed.

‘The elves say that sometimes lightning can strike twice. They call it… Bugger, I’ve forgotten. The noose of fate?’

‘The loop,’ he corrected her. ‘The loop of fate.’

—Baptism of Fire

Individual destinies unfold cyclically as well – Geralt’s and Ciri’s intertwined fate moves inexorably toward the completion of a well-known arc. Geralt must complete the search for the Grail that disappeared after briefly revealing itself to him in the form of a little girl who made it clear that he cannot avoid what accepting her presence in his life means. What she, the Grail, represents is healing through love. The journey in this arc is always about internal transformation – once this is complete, as in Rivia, Geralt’s life in the profane time ends. He has returned to the beginning within himself, has re-entered Myth and become part of it. History’s vicissitudes no longer hold any sway.

As for Ciri who needs to move through Mythic Time, who needs to become legendary matter in order to be able to be present at the beginning (and ‘end’) of hers and Geralt’s tale, she can only do so because she retains her ancestors’ pre-rational access to the weave of storytelling (and the author’s blessing). As a meta character, she is literally made of the same stuff as elves, unicorns, dreams, and fairy tales.

What I am trying to say is: in a demystified story, elven – and Ciri’s – philosophy is meta-aware because it reflects an ontological nature outside of The Witcher’s Historic Time.

Aarhenius Krantz believes deeply that to travel to other places, times, universes, ‘A way will be found. But it will demand utterly new thinking, a new, original idea that will tear apart the rigid corset called rational cognition that restricts it today…’[4] Except, it might not be anything more or less than saying: ‘I wish.’ And seeing where it takes you. For the ‘modern man’ – physics! For the ‘archaic man’ – storytelling. The new is ever only the long forgotten old. Learn. Make use of your sources. The scholar Katarzyna Łęk[5] proposes that the exemplary history Mircea Eliade describes is the Arthurian mythos. That is the central template at the beginning. I would go further: the centre is absent, which means it is everywhere, including in Arthuriana. Any myth will do. Sapkowski, reportedly, knows them all.

It is evident elves know the way. Tolkien identified it as the elves' foremost craft – Enchantment, the creation of Secondary Worlds. And, crucially, he argued that this desire for living, realized sub-creative art is not just what elves do (entering and living the myths) but what they are. In The Witcher, they are simply constrained for Plot purposes by Sapkowski having thrown away the key during the Conjunction. Trapped in Historical Time, his elves yearn to return into a different kind of time, a way of being where death is reversible and rebirth virtually instant. (We will return to this in Part 4.) It is an attempt at reclaiming an essence that does not exist and, hence, will always exist, for as Leśmian put it: we exist as echoes of echoes, reflections of reflections.

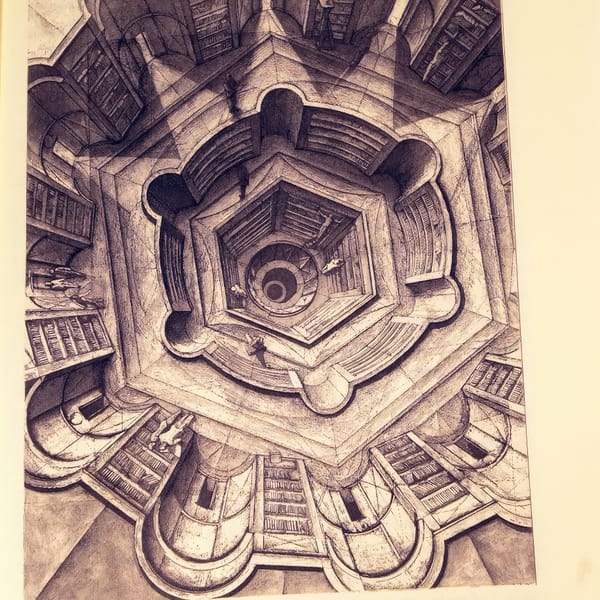

But what might existing as echoes and reflections across the mirror tunnel of storytelling actually look like for the elves? Sapkowski leaves clues across his body of work not just in The Witcher. Before we can grasp how (and why) Ciri moves through the archipelago, we should think about how archetypal figures persist, vary, and renew themselves across different retellings. How can the same tale unfold endlessly without ever reaching an end?

Footnotes

https://angelus.com.pl/2015/07/sapkowski-podbija-rumunie/ ↩︎

Sapkowski, A. The Last Wish. ‘The Edge of the World' ↩︎

Sapkowski, A. The Lady of the Lake. Chapter 7 ↩︎

Sapkowski, A. The Lady of the Lake. Chapter 7 ↩︎

Łęk, K. 2005. Arthurian Myth in the Cycle of Works About the Witcher Geralt by A. Sapkowski. (Mit Arturiański w Cyklu Utworów o Wiedźminie Geralcie A. Sapkowskiego) ↩︎