Archetypal vs Sci-fi Take on Time in The Witcher | Part 3 of 'History and Fantasy'

What could 'eternity' mean for the Aen Elle in a meta fantasy? The Conjunction closed the door into infinite possible worlds, trapping the elves in The Witcher's. Power over Time might be better thought of not in sci-fi terms but as of being able to cross the border between Myth and reality at will.

A Legend’s Archetypal Existence

Q: It's about the ending itself. Why Galahad? He found Ciri and in the Arthurian myth he found the Holy Grail. What does that mean? Why do Geralt and Yennefer smell apples at the end? Aren't there too many references to "The Mists of Avalon"? (Ciri's stay in the world of elves, Tor, Lady of the Lake, boat trip, etc.)

A: These are not references to Bradley, but to the legend, myth, the topos, the archetype. That was my intention, that was my artistic concept and vision. My right. What can I do, that mythical Avalon is an archetype, a perfect place to give tired heroes a well-deserved peace of mind? What can I do about the fact that Avalon is an archetypal island that can only and symbolically be reached by boat? What can I do about it being an island of apples, because in Welsh Afallen is an "apple tree"? So what is Avalon supposed to smell like? Chanel number five?

—A. Sapkowski, 2001, Q & A with Polish Fans

The Fantasy genre makes heavy use of character archetypes and topoi. Call it the template ‘at the beginning’ that authors like alchemists set off to transform and distil from. Archetypes summon narrative necessity which invisibly guides the Plot whether the author decides to honour, subvert, or re-interpret the archetype. The passing of the Faërie (the primeval world), for example, is a classic. ‘A greedy man breaks into the land of elves and imps covered with dense forests, destroying everything that is important and sacred to other races. This is the pattern created by Tolkien – the story of an arcadia invaded by a demon,’ notes Sapkowski.[1] Faërie Time is another staple, appearing in scenes of dreams, death or near death, or journeys into the Unconscious; signalling the breaking of the Sacred into the Profane.

As in Avalon – the apple island, sanctuary for mythic things no longer fit for Historic Time – so in Tir ná Lia (inspired by Tír na nÓg and analogues).[2] There are signs that Ciri comes to a place where a different kind of Time dominates:

- time feels ‘timeless’ in Faërie and one exists as if outside the durational flow;

- unicorns[3] continue to exist in Faërie, remaining for the inhabitants of Sapkowski’s Neverland the representations of fairy tale, continually endowed with its power (the power itself being meta: to move, that is to exist, in different places and times (storyworlds));

- as inside Tor Zireael, Ciri is able to communicate with the dead Vysogota here and we are unable to ascertain if her subconscious is warning her or if the experience is real.

Think of the Land of Elves as of a time not a place. Or a ‘place’ in a particular kind of time: Mythic Time, or illud tempus. Tir ná Lia drifts in a halted moment where archetypal logic still operates. Existence here resembles death, dreams, the Unconscious, while the Plot is, indeed, associated with all three. True to its archetype, Tir ná Lia demonstrates what existing closer to Mythic Time looks like and, perhaps, what the tribe of elves who ‘left for a more interesting reality’ found so interesting. The elves’ way of being here is closer to their nature as mythic beings than in Neverland. Except the euhemerizing curse of the tale they are in follows them here as well.

In The Witcher, elves – particularly the Aen Seidhe – seem like fallen immortals, having come some way since Tolkien’s landmark conception of the Noldor. (Perhaps they are the elves who chose not to return to the West, nor to fade, but broke out of the confines of Arda?) They are archetypal, straight from Tolkien and RPGs, but profaned just like everything else. The Aen Elle retain a more legendary impression, but the author’s modus operandi dips their motives and emotions in the same sauce of history’s debased realism. It is nearly impossible for anyone to remain truly unknowable and mysterious in their emotions, motives or motions. To the extent that the cycle revolves around diagnosing the human nature, it is precisely human nature that finds reflection in other races. The baseness in humans ‘infects’ other beings in this story because the method of approaching the fairy tale as when it was first told prescribes this. Not even unicorns escape de-idealization. Elves may consequently be noble, but they too can be noble bastards. Mankind has fallen into Fantasy and the fabled and the fantastic have fallen into History.

Unlike our protagonists though, the elves’ philosophy seems self-aware of this predicament. I would argue that at least the elven Elders and Knowing know they exist in an euhemerized reality and yearn to escape back into fairy tale. Their philosophy embodies Mircea Eliade’s theoretical framework within The Witcher world, signalling the closing of the Ouroboric circle in which Sapkowski moves from euhemerization into restoring the power of legends. Let me show you how that could work.

Elves are what Leśmian would call the ‘nieistniejące’ (non-existent): entities that do not exist in conventional material sense but possess genuine reality through linguistic creations and imagination. Elven roots, after all, stretch back much further than Tolkien’s portrayal which made them the hallmark of fantasy literature. Their mythic analogues are innumerable and defy clear categorisation (was Alberich of the Nibelungs, a cognate of Oberon and Auberon, a dwarf or an elf?). Therefore, I want to think about this through the concept of ‘archetypal variants,’ which seems baked into the way Sapkowski involves various fantastic figures in his story. Perhaps you have heard something about a Warrior, a Wizard, a King, a Lover, a Chosen One? It works also in higher granule: Ciri as an amalgam of Morgana, Bradamante, Nimue/Vivianne, and the Triple Goddess. Ciri, in her own storyworld, and for one elf in particular, as Lara reborn and Lady of the Lake, or, for the superstitious humans, as Falka re-incarnate, or, for the Skelligeans, the Lion Cub. Ciri herself, from the perspective of Mythic Time, is ‘nieistniejące’. She takes on legendary identities and is attributed them. She chooses to be called Ciri of Vengeberg just before Yennefer herself passes into legend. Ciri is ‘just a legend.’

Reflections within reflections.

We also witness the idea at play in the way Emhyr and Auberon are variants of each other, as are Cahir and Eredin, Avallac’h and Vilgefortz, Lara and Ciri.[4] These characters exist in a different time and place but share descriptive and functional conditions (though not equivalency) while yielding divergent outcomes in the Plot of The Witcher. They parallel each other structurally as archetypal analogues. Yet we still remain within the confines of Sapkowski’s tale. More broadly, many of The Witcher’s characters, particularly its elves who make a dent in the Plot when meta-fictionality becomes more complex and relevant, are mythical figures from folklore. Sometimes doubly so, since the unicorns and the Wild Hunt are mythic for both the mankind in The Witcher and on our Earth. Why not assume then, that figures like Auberon and Avallac’h are mythic figures rather than being merely based on them?

Let’s imagine that pre-Conjunction, the Alder King was able to exist as the archetypal Fairy King manifesting as Auberon Muircetach, Alberich of the Nibelungs, Shakespeare’s Oberon, Oberon from the Huon de Bordeaux, etc. These are manifestations that bear different names across different story-streams but remain fundamentally the same idea in Mythic Time. The Witcher is but one possible time and place in which the archetype can manifest, a moment of spotlight in literature. If narrative necessity calls, a variant shall re-enter a story that requires it in one name or another. (Analogously to witchers who will always be needed.)

‘From the point of view of eternal repetition, historical events are transformed into categories … In a certain sense it can even be said that the Greek theory of eternal return is the final variant undergone by the myth of the repetition of an archetypal gesture, just as the Platonic doctrine of Ideas was the final version of the archetype concept, and the most fully elaborated.’

—Mircea Eliade, The Myth of the Eternal Return

In the realm of Myth, where stories are created and perpetuated, archetypes rule. Every new manifestation in a tale told by the fireside varies them. Sapkowski explored this principle in Maladie (1992), where Tristan’s and Iseult’s love legend summons its successors for archetypal positions that can never remain empty. Morholt (an antagonist) and Branwen (Iseult the Golden-Haired’s handmaiden) are summoned from death (that smells like apples) by the tale's need to complete itself. Narrative necessity manifests as merciful Providence that brings together two souls with unhappy fates. Both characters were merely instrumental in the classic love legend of Tristan and Iseult; a collateral damage. But in their meeting, love awakens, bringing them closer to the love legend’s intrinsic meaning, and when a force arrives that seeks to destroy the legend (prevent the famous beryl tomb, erase the lovers from collective memory), Morholt takes up Tristan’s role. Asked his name, he answers ‘Tristan’ and steps into the tragic lover’s image, becomes an archetypal variant, and fights to save the legend, beginning a new cycle of an eternally recurring pattern.

Maladie suggests that legends can only survive, be reborn, and continue unfolding (endlessly in infinite variety, as per Leśmian) if people keep entering them. Tristan’s and Iseult’s legend requires the roles of victim/victor, Irish/Cornish, tragic lovers. Morholt and Branwen, secondary characters unessential to the Plot (or are they?), shake off their original identities and begin a new iteration: 'To hell with the healthy!' Their love sustains the hope in the imperishable power of the legend.

Now, as a self-aware archetypal entity inside a tale, would you not like to be able to shake off the unfavourable or unsavoury form that you obtain in someone else’s Plot? Reality consists of competing narratives; even within particular legends.

The story ends with Morholt observing the incoming ship's sails: 'The sails were dirty. Or so it seemed.' This leaves the legend in perpetual limbo. Classically the sail colour determines Tristan’s fate – death of grief as his wife, Iseult of the White Hands lies to him about their colour. But in this iteration everyone is aware of their existence inside a legend and can hear each other’s thoughts. Tristan regrets not being able to love Iseult of the White Hands for herself and, finally, means her when he calls out that name: Iseult. Differently, without resentment, without longing for another. And we witness hearts awakening to compassion. (Just as in the peristyle between Ciri and Avallac’h, by the way.) And Iseult of the White Hands, who knows what awaits her, who desperately tried to change the legend, realizes that nothing can be changed… well, almost nothing. She extends compassion in return and tells Tristan the sails are white, that Iseult the Golden-Haired is coming, and Tristan, trapped in the Plot of this legend, dies as he was always meant to, but happily.

The legend’s archetypal shape does not change, but we also never learn the ‘truth’ of this iteration because Morholt and Branwen leave before discovering it. The legend can still pass into collective consciousness as Iseult of the White Hands having lied and Tristan having died from grief. As can other variants. In mythic reality, contradictory versions coexist without resolution. Perception is colonized by expectations and truth becomes plural.

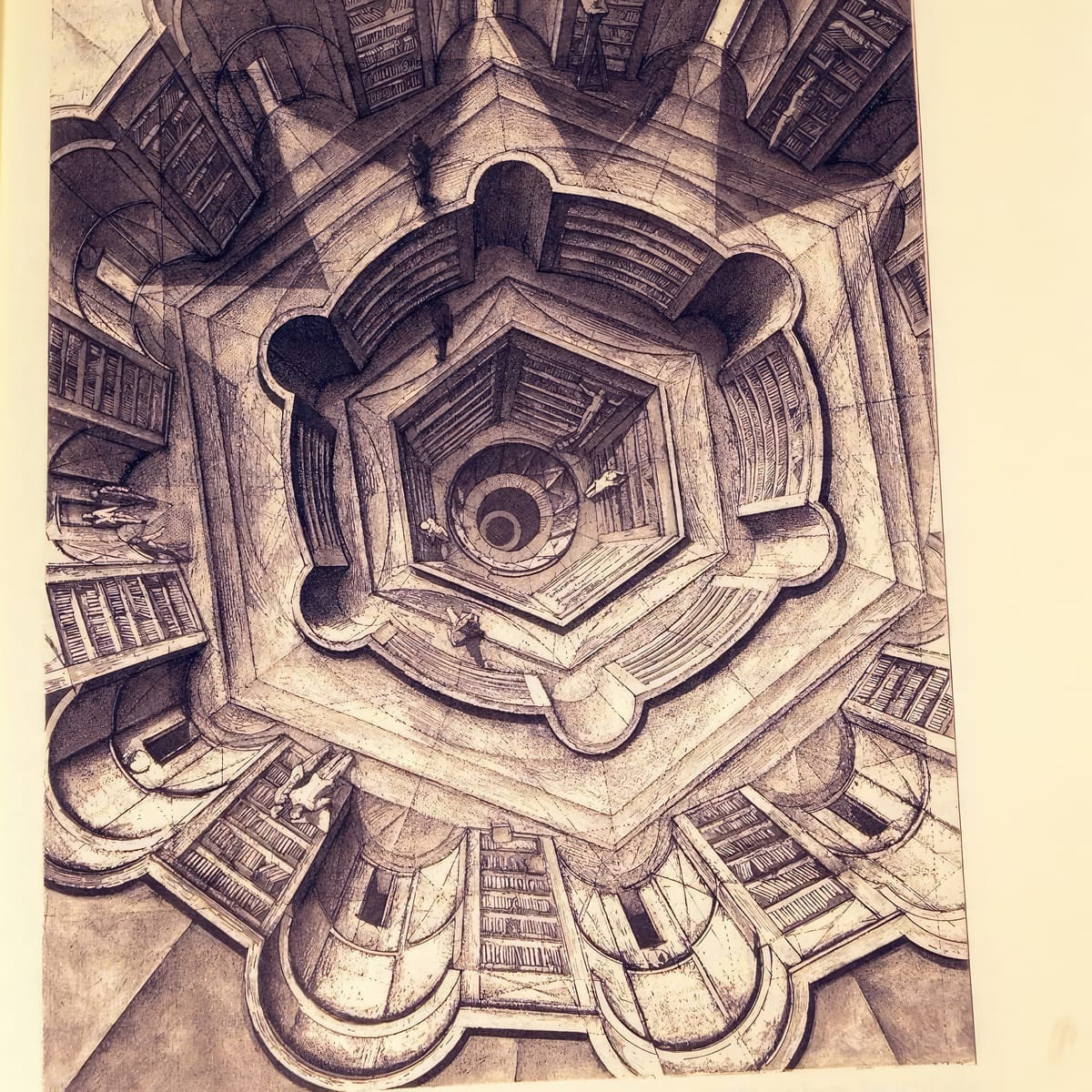

The fairy tale unfolds itself endlessly inside a mirror tunnel.

Mythic Eternity

‘How can you claim that something is ending? How do you know whose destiny is destruction and whose eternity? What entitles you to speak of destiny? Do you actually know what it is?’

—Sword of Destiny

‘Why be impatient?’ Avallac’h pouted his lips slightly. ‘What can we gain by haste?’

‘Eternity.’ Eredin Bréacc Glas became serious. Something shone briefly in his green eyes. ‘But that’s your speciality, Avallac’h. Your speciality and your responsibility.’

—Lady of the Lake

When elves speak of eternity, I read them as speaking of a way of being. To inhabit eternity as legends is to exist through time as variants of archetypes known to all from shared tales that can be summoned at will; who, if one was inclined to imagine such a tale, can also self-summon. Such eternity would involve inhibiting all moments simultaneously not successively. (In truth, of course, there is no narrative to tell about with nieistniejące entities without a perceiver – an author and a reader. But let us consider.) Such a way of being would forever beam with hope for new beginnings.

‘Ouroboros symbolises eternity and is itself eternal. It is the eternal going away and the eternal return. It is something that has no beginning and no end. Time is like the ancient Ouroboros. Time is fleeting moments, grains of sand passing through an hourglass. Time is the moments and events we so readily try to measure. But the ancient Ouroboros reminds us that in every moment, in every instant, in every event, is hidden the past, the present and the future. Eternity is hidden in every moment. Every departure is at once a return, every farewell is a greeting, every return is a parting. Everything is simultaneously a beginning and an end.’

—Lady of the Lake

The Ouroboros symbolizes elven philosophy. As a legend, rather than progressing from event to event in a single historic narrative, you are able to exist as an archetypal figure in a near infinite range of possible stories that could be told; accessing the eternal, shifting sea of Plot that contains all moments – times and places – always. (Perhaps the Knowing Ones’ ability to know past, present, and future is a remnant of a mode of being in which the elven sages did not just glimpse at time but inhabited it?) The Alder King, who has many faces, is describing eternity while imprisoned in his biography in The Witcher. 'Every moment contains past, present, and future' should mean simultaneous access to all three, but for Auberon it has become mere philosophy.

Before the Conjunction, Auberon could die in one variant and manifest in another while maintaining a sense of self (memories). Now Auberon experiences himself as a mortal individual who will end finally as Auberon of The Witcher cycle, despite his archetype persisting elsetime inaccessibly. He is cut off. His only eternity is to be found in his dead daughter and her distant descendant – Ciri. Elves might know they are in a story and that their archetypal selves appear in infinite other times and places, but this consciousness, these memories, this ‘me’ ends.

Troubles began with the Conjunction of the Spheres; the primordial act of Creation by the author from Łódź. Elves used to move (that is ‘to exist’) between worlds quite freely while Mythic Time prevailed. The Conjunction changed the ease with which they were able to access the Gate of Worlds, Threshold of Time (an abstract principle given a concrete outline) despite their inherent ability remaining intact. They were effectively rendered quasi-mythical (unlike the unicorns with their own archetypal role) as they were constrained to a single story the topoi of which necessitated the role they are to play – a role that has been foretold and retold many-many times. The elves always leave the world behind before its eventual, inevitable rebirth.

If before the Conjunction their civilization (the concept ‘elves’) could span multiple realities as a unified ontological category, i.e. they could move freely, now they have become fixed characters incapable of accessing other incarnations. For example, Auberon cannot reach the moments where he is Oberon married to Titania; Avallac’h cannot access the versions of Time where Lara stayed with him. Would such an Avallac’h still be himself if he had access? In some sense yes (same archetypal mix of Merlin, Pygmalion, Tristan, etc), in another no. Accessing Time is not about changing history within one timeline, though. Currently, elves are forced into historical existence with irreversible loss, aging, death. Using Ard Gaeth for all of their sake would not fix their history in the tale of The Witcher, but it could release them from being permanently bound to a history. I think the elves want to escape The Witcher as their terminal fate.

To exemplify what I imagine could have been possible before the Conjunction, imagine a scenario where Auberon needs counsel from a sage who died 200 years ago relative to his present moment.

Within Historic/linear constraints (current state), the sage is gone, existing only as a historical record, memory, perhaps as something a Knowing One can scry. Auberon can access information about what the sage knew, but he cannot have a new conversation with him as he is; at least not without necromantic shenanigans. In Mythic/non-linear freedom, the story of the sage is not set in stone: there is a version where the sage dies at the same moment as in the story where he has been dead for 200 years, there is a version where he exists for as long as Auberon, there is a version where the sage never existed, and various in-betweens. The sage and Auberon exist simultaneously as possible narrative elements. Everything co-exists before composition: before the appearance of an observer – the author – who sets one version on paper. In Mythic Time though, the commitment of one instant ‘onto paper’ (playing it out) does not erase the co-existence of others either; they remain possible even when that one version is being played out.

Only myths and fables, Borch Three Jackdaws tells us, do not know the limits of possibility.

Effectively, Auberon can choose to have that conversation with the sage in a set of possible worlds where the sage remains alive because in Auberon’s present moment, this conversation is what is necessary for the Plot. Narrative necessity inherent in Auberon’s need calls for the making of an archetypal move in storytelling, which enables for an opportunity to summon itself out of the archipelago of moments that unfold themselves endlessly.

Auberon would not be ‘travelling back in time’ and ‘changing the past', because we are not operating within the laws of physics and rational-scientific reality in The Witcher. Auberon manifests inside a story-variant where the sage exists, simply accessing a different moment where past, present and future have different relationships than in a version where the sage is dead. The Schrödinger's Sage is simultaneously Alive and Dead in Mythic Time, as are all legendary entities. Nieistniejące, remember?

Within Historical Time, this is paradoxical because either/or, but within Mythic Time it's normal. Both/and. Odin sacrifices himself on Yggdrasil and is simultaneously alive and dead, Odysseus descends into Hades and speaks with dead heroes, Celtic heroes visit Otherworlds where time flows differently and centuries pass in a day, Gods appear in multiple places simultaneously and do contradictory things. Causation in Mythic Time is symbolic and thematic, as we observe ideas at play. The story is our mind’s imposition and the characters in it are made of story-stuff not materia.

Application In-Universe

Alright, great, but inside a story, what does this look like day-to-day? Sounds nuts.

Well, it does not look like this: Auberon wakes up, has breakfast, talks to the living sage, then tries to talk to the dead sage, and experiences no contradiction. Events in Mythic Time do not follow linear causation. The narrative obtains dream-like fluidity. If I wanted to write about this, it might result in a set of moments connected by a through line (a need, a question, a puzzle, etc), not A-follows-B-causes-C events. It might not result in a classic novel. Likely the written word, which requires at least some logical follow-through, is not the best way to convey such a mode of being at all. Visual media might be better. Traditional prose resists pure mythic ontology. A book would start employing scaffolding like parallel worlds or incarnation cycles, because you need a concept on which to hang the moments. Sapkowski uses the elven towers, Ciri’s visions, dreams, the archipelago metaphor, parallelism (e.g. Toussaint vs Tir ná Lia, characters in Neverland and Otherworld), etc. All are scaffolding to let mythic logic bleed through into a seemingly historically unfolding narrative and the Plot of The Witcher. Otherwise you become avant garde; or a mess. Interesting, but not for everyone.

Alright, alright, but you are asserting this as in-universe lore! You are saying this is the way of being the elves and other fantastic entities had before the Conjunction of the Spheres (and we don’t even know what that was)!

What was before the Conjunction, though? Does it matter? A bard would say: I don’t know, nothing in particular, or everything possible. Pass him another bowl of soup and he might tell you; or he might not. Many tales continue unfolding independently. For before the Conjunction was what Tolkien calls, ‘the Cauldron of Story.’

Sure, but wouldn’t that mean that it is impossible to speak of the elves’ past before Geralt’s narrative begins?

Well, yes, I guess in a sense I am saying this. It is not without reason Sapkowski does not answer questions about the things he has not written about. Everything that is not on the page continues existing as a possibility; saying more would collapse an idea into one historical account. Many things are implied and can be inferred from the rest of the text, and many things are left secret for a reason, but these too remain as unwritten possibility. The Witcher’s conclusion is making a point about the open-endedness of legends. The appropriate response is silence and openness. X might be but that would require you to tell a new story. Storytelling is never ending.

If a tale makes its concern to first demythologize and then show the reader how myths are born, and what Never-Neverlands and dreams are made of, then it is not outlandish to talk about the ontology of the possible as if it were a logical explanation for the un-written, implied parts of the mythical entities’ history. Elven ‘history’ simply cannot be historical; it is non-existent, mythical, and, hence, infinitely possible.[5]

‘Neither our race nor our power draws its strength from rationality. In spite of that it has endured for tens of thousands of years.’

—Baptism of Fire

I like my theory because it frees me from having to contend with paradoxes of time travel that are characteristic of fantasy universes that cling to sci-fi materialism. In literature, by contrast, everything remains possible. With a little talent and skill, naturally.

Footnotes

A. Sapkowski & S. Bereś. 2005. Historia i Fantastyka (History and Fantasy) ↩︎

Lia Fáil translates to ‘Stone of Destiny.’ In the Grail myth’s retelling by Wolfram von Eschenbach, which seems closest to Sapkowski’s heart, the Grail is a stone, not a cup. ↩︎

In The Witcher, unicorn is the other thoroughly mythical animal besides the dragon (variant of the Ouroboric Serpent, e.g. the Germanic Nidhögg). ↩︎

By contrast, Angoulême and Ciri, Fringilla and Yennefer, Vilgefortz and Geralt are foils, shadows, same-world mirrors that function within a single Time. ↩︎

You can go on euhemerizing forever, all the way down the rabbit hole, until nothing is left of wonder, not even in the unicorns. I am not sure what the pay-off would be, though. ↩︎