Who is Nimue, How Does Ciri’s Power Work, and Why Lady of the Lake Confuses Readers? | Part 4 of 'History and Fantasy'

The Lady of the Lake confuses The Witcher's readers because Nimue is us – the lighthouse that completes the story. Ciri, adrift in timeless mythosphere, searches for one more moment with Geralt and Yennefer, waiting for someone to believe. For a fairy tale ceases to be just a tale when readers do.

Who is Nimue and Why the Reader Matters?

‘If I dream something,’ she said, going back to the subject and drying herself with a towel, ‘what guarantee is there I’ve dreamed the true version? I know all the literary versions of the legend, from Dandelion’s Half a Century of Poetry to Andrei Ravix’s The Lady of the Lake. I know the Honourable Jarre; I know all the scholarly treatments, not to mention popular editions. Reading all those texts has left a mark, had an influence. I’m unable to eliminate them from my dreams. Is there any chance of breaking through the fiction and dreaming the truth?’

‘Yes, there is.’

‘How great?’

‘The same chance the Fisher King has.’ Nimue nodded towards the boat on the lake. ‘As you can see, he keeps on casting his hooks. He catches waterweed, roots, submerged tree stumps, logs, old boots, drowned corpses and the Devil knows what else. But from time to time he catches something worthwhile.’

—Lady of the Lake

Most readers stop with Lady of the Lake at some point, confused: who are these people? Why are we suddenly doing literary research? And dreaming should not qualify as evidence by the way. Where are Ciri and Geralt? Is this some kind of Arthurian joke? So! Extra!

Your pain and confusion is, unfortunately, the point.

The Witcher has a triple narrative frame:

- The 'actual' events, overgrown with fabrication and fantasy

- Nimue studying the legend of Ciri and Geralt 150+ years post-'fact'

- Ciri recounting everything (including Nimue) to Galahad in some version of Arthurian Britain (itself a mythic space).

Finally there is the meta layer: all of this is happening in a story a Pole from Łódź made up. These frames blur into each other. Without a stable bedrock The Witcher is only a story reflecting stories, all conjured by an author who tells us: ‘To be completely frank, they are just letters on paper.’

All we see or seem

Is but a dream within a dream

—The Lady of the Lake, Chapter 2, by Edgar Allan Poe

(Omitted in the English translation.)

Stories hinge on interpretation. They live through readers, becoming mythology when readers breathe meaning into them.

Sapkowski introduces the figures of Nimue and Condwiramurs into the Plot in order to demonstrate legendary matter’s fluid and cyclical nature. Lady of the Lake is the culmination of his play with the darling tropes of the Fantasy genre and it caps with myth-making. The author has spent the whole series tearing the fairy tale down just to reaffirm storytelling’s imperishable, eternal nature by letting the fairy tale return in the end. Only naturally then, we follow the obsession of Nimue, a self-fashioned variant of the archetypal Lady of the Lake, in her search for her Grail – the ‘true’ story of Ciri and Geralt. Like Morholt in Maladie, Nimue enters the legend of The Witcher – by reading it. With her search she completes the tale anew and births a new variant in her understanding, as does every reader with each retelling.

A hundred years after the pogrom in Rivia, Ciri and Geralt, as legend and reverie, feature solely on the margins of Neverland’s Historical Time. Not a single portrait of Ciri survives. She has become, quite simply, a figment of the artist’s imagination. People have attributed to Geralt and Ciri a lot that (probably) never happened, but which could have conceivably happened to characters of their type. Nimue, though, firmly believes Ciri must have existed in Historical Time, because she once saw an ‘apparition’ while… indisposed; of an ashen-haired girl on a black horse hanging over a lake. Consequently, she concludes that the legend is being settled at this very moment – by the grace of her belief which keeps the legend alive as she searches for her truth around 150 years after the supposed historical fact.

The legend has been settled many-many times, is being settled right now, and will continue to be settled for long to come. Or so one hopes.

I see a mirror tunnel, carved, it seems

In the underground of my dreams, menacing and enchanted,

Lonely, never touched by a human sole,

Not knowing the seasons, frozen in time.

I see a fairy tale in a mirror, where instead of the sun,

A procession of candles watches over the long forgotten dead,

A fairy tale that endlessly unfolds by itself

In order to never reach the end...

—Bolesław Leśmian, Translation by Krystian Kościelski

When something anomalous but remarkable appears in our lives, it puts us in a different frame of mind and time: a rift opens out of which so far unconsidered possibilities emerge. In such fairy tale-like moments, we touch something sacred, profound and more persistent than the wearisome day-to-day rhythm of life. We return, as Eliade puts it, to the beginning where every piece of reality was inherently invested with meaning. The legend of Ciri spoke to Nimue as a girl, she saw its likeness many times in dreams, and once, she encountered it even while awake. She is not alone in this.

Fairy tales cease to be just tales when people start believing in them.

We encounter mythical matter on daily basis; we just don't always mine it for its worth. Medieval knights tell stories about a demon they saw, the French innkeeper remembers a strange girl who awoke motherly sentiments in her, Aarhenius Krantz, a scientist, is struck speechless by an appearance so sudden that he cannot prove but is inspired to consider and example of the plausibility of interdimensional travel. New stories are born out of such experiences. It is the same as with having read a good book: your imagination is being engaged and you are creating. Are the resulting stories of an ashen-haired girl with a scar on her cheek distortions of one ‘true history’? Or is a mythic entity's manifestation across multiple moments exactly what creates new legendary matter as myths always have?

Interdimensional travel as a scientific concept might not be as helpful for understanding The Witcher as it seems. For understanding what Nimue and the reader are doing, and why it works, we should understand what Ciri is.

How ‘a Ciri’ works?

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep

—The Lady of the Lake, Epigraph, by William Shakespeare

(Omitted in the English translation.)

Q: Are Ciri's travels related to travelling in the shadows (Roger Zelazny's ten books on Amber and the Courts of Chaos) and was the passage of Ciri through the Tower of the Swallow a passage through The Pattern? Did you rely on Zelazny's work when writing the saga?

A: Of course I know and like the "Amber" series very much, I never hid the fact that Roger Zelazny was an example of literary mastery for me, I read it long before my own debut as a writer - to which he largely inspired me. However, let me note, seriously, that fantasy – and the mythical literature at its root – is simply full of such "Shadows", "Patterns", "parallel worlds" and thousands of ways to teleport. No one can claim a monopoly here. So I reject the suspicion of "influence" – my Towers and Ciri's abilities – even if not unique – are in my opinion "mine" enough. So much so that I will remind everyone of Michael Moorcock's Disappearing Tower without fear – seemingly even more similar to the Tower of the Swallow than The Pattern.

—Andrzej Sapkowski, Meet the Author Interviews and Q&As

In Ciri’s veins flows Hen Ichaer, the holy Elder Blood. The Blood of Elves. Ciri is a descendant of those elves who in her Historical Time live only in legends that describe their extraordinary magical and prophetic abilities. Lara Dorren, a Knowing One and Ciri’s ancestor, belonged to this tribe and in her descendant, the Swallow, the elves see the one who will lead them out of the wasteland of their existence in Neverland’s history.

Ciri’s fate is to become, as per her own words, ‘just a legend.’ It is her lot from birth. Her origins render her the same stuff as elves and unicorns – a fairy tale. Mutated, of course, as Sapkowski mutates all fairy tales. And despite the flattery in being deemed a legend, such existence, too, can be a prison all on its own. The connection to Geralt that Ciri chooses is the cry of a flesh and blood girl, who is born into history and subjected to its innumerable sufferings as if she were born a martyr, a symbol, of what happens to beings who do not belong in the mundane circle of life. Who do not belong in any place at all. Not really. Ciri, too, fills a plot function.

‘We’ve waited long. Fearing but one thing: whether you’d be able to enter here. You were. You proved your blood, your lineage. And that means that your place is here, not among the Dh’oine. You are the daughter of Lara Dorren aep Shiadhal.’

—The Tower of the Swallow

When Ciri enters the elven tower Tor Zireael, she proves her origin as of archetypal, legendary matter. She moves beyond historical time and place into the timelessness of mythical reality and is given a new name virtually instantly. Loc’hlaith. Lady of the Lake. A name as much as a category.

‘But when asked if we might approach and from proximity gaze on the Tower or propria manu touch it, Avallac’h laughed. “Tor Zireael,” he spake, “is for you a reverie, and reveries may not be touched. And a good thing it is,” he added, “for the Tower serves only the few Chosen, for whom the Threshold of Time is a gate of hope and rebirth. But for the profane it is the portal of nightmare.”

—The Tower of the Swallow

Ciri is one of the Chosen who retain the ability to exist in mythic mode between histories. You have to give a little of yourself to the mists, become hazy enough of a figure to seep through the door frames. Because how do the books describe the practice of moving between places and times?

The elven towers are like anchors that tie passage into Mythic Time to material-historical reality. They are relicts of their builders’ pre-Conjunction way of being. Perhaps they even exist at all because of the changed condition of reality post-Conjunction? In order to guess at how many more there might be, one should read more good stories. Because forget ‘parallel worlds’ as planets; that is a way of depicting reality that leads the rational mind onto a very particular path. The Witcher has never been an example of scientifically believable worldbuilding. In The Witcher, we are swimming in literature. Let us proceed with the letters on a page and worlds locked in place by the written word.

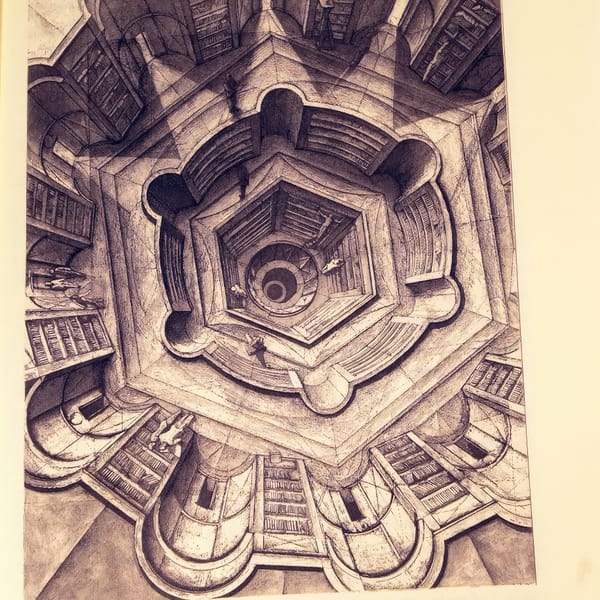

When Ciri rides into Tor Zireael, she first experiences soft, black darkness; as in a dream in the very beginning before imagination could begin weaving its magic. Then geometry emerges:

At first, the inside of the tower reminded her of Kaer Morhen – the same long, black corridor behind a colonnade, the same unending abyss in the perspective of columns or statues. It was beyond comprehension how that abyss could fit into the slender obelisk of the tower. But she knew, of course, that there was no point analysing it – not in the case of a tower that had risen up from nothingness, appearing where it had not been before. There could be anything in such a tower and one ought not to be surprised by anything.

The colonnade she had ridden into blazed with an unnatural brilliance.

Kelpie’s hooves rang on the floor; something crunched under them. Bones. Skulls, shinbones, ribcages, thighbones, hipbones. She was riding through a gigantic ossuarium. Kaer Morhen, she thought, recalling. The dead should be buried in the ground… How long ago that was… I still believed in something like that then… In the majesty of death, in respect for the dead… But death is simply death.

She rode into the gloom, under the colonnade, among the columns and statues. The darkness undulated like smoke. Her ears were filled with intrusive whispers, sighs, and soft incantations. Suddenly brightness flamed before her, as a gigantic door opened. One door opened after another. Doors. An infinite number of heavy doors opened before her without a murmur.

Kelpie went on, horseshoes resounding on the floor.

The geometry of the walls, arcades and columns surrounding her was suddenly disrupted; so confusingly that Ciri felt dizzy. She felt as though she were inside an impossible, multifaceted solid, some gigantic polyhedron.

The doors kept opening. But now they weren’t delineating a single direction. They were pointing to infinite directions and possibilities.

—The Tower of the Swallow

Ciri is inside an impossible architecture where all possible times exist simultaneously. She sees things which have happened, which are happening, and which might yet happen. As she nears the end of her trip, she discovers she can also converse with Vysogota who has passed on into another plane of existence. It is The Threshold of Time – like Death, like Dreams, like the Unconscious. Like Myth. It opens into Time. The doors keep cracking open ‘pointing to infinite directions and possibilities.’ Mythic reality from the inside looks like a polyhedron of reflective surfaces; each a potential story-moment.

Two mirrors that feel the airiness of their depths,

I set one against the other with haste,

And I see a series of reflections shuttered into eternity,

Each farther one a congealed echo of the last.

—Bolesław Leśmian, Translation by Krystian Kościelski

The barrier between places and times is like glass, shattering into rainbow sparkles when breached. ‘The image blurred and shattered, as painted glass shatters, suddenly fell to pieces, disintegrated into a rainbow-coloured twinkling of sparkles, gleaming and gold. And then all of it vanished.’ To enter another reality is to tear the canvas, crack your reflection in the mirror as you become part of another variation of possibilities. Or perhaps each world is like a bubble, shimmering and fragile, floating in the mythosphere and containing variations of the same moment?

Michael Ende's Temple of a Thousand Doors works identically: hexagonal rooms, endless doorways, accessible only through genuine need. Both the Temple and the elven Tower are narrative devices that signal their own nature as thresholds where historic realism ends and story-logic takes over. We have already seen what Mr Sapkowski thinks of analogies to Zelazny, but see C. J. Cherryh’s Morgaine tetralogy for object level take on Gates anyway. All authors are fundamentally drawing from the same storytelling principle.

The Tower of the Swallow provides Ciri with handrails: she could pass into any reality but the tower-builder has linked it with a particular beginning – one she is drawn to both by the legend she carries in her blood and by someone else's desperate need calling to her. There is a place and time, where she is needed. This attraction mirrors the narrative necessity inherent in her own Plot – journey into the Faërie, the Fairy Forest of the Unconscious, is made for transformation. Once she has come to accept her heritage, she begins to navigate without the Tower’s geometry of cached realities inside the soft, black darkness. The Tower allowed her to peek at what lies behind the doors of imagination; itself, perhaps, a means of structuring and locking down for perusal the many conceivable possibilities. Without its help, Ciri simply ends up in a place within an equally large variety of possible places, unless she knows what she really-truly needs. She is learning her elven nature by learning to wish: ‘Perhaps not imagine places or faces, but strongly desire... very strongly, right from my belly...'

Magic in its most primordial form starts with: ‘I wish…’

Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back — not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other — is the talent of the master. The Cosmic Dancer, declares Nietzsche, does not rest heavily in a single spot, but gaily, lightly, turns and leaps from one position to another.

—J. Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

Ciri’s movement is described as ‘sailing’ in the ‘labyrinth’ or an ‘archipelago’ or a ‘sea.’ We witness the places briefly, but we have very little understanding of time. Ciri has escaped into time once before, and in that moment she became as if dead for The Witcher storyworld. Why? Because she entered Mythic Time that spirals invisibly around any particular Historic timeline that hosts the Plot that we follow. She undid herself as a specific Ciri and became a Ciri-potential.

From the perspective of mythic timelessness then, I think that when Ciri appears to the Teutonic knights and the French innkeeper, she is not travelling through these moments sequentially but is manifesting across them simultaneously as a mythic intrusion into historical reality. From Ciri’s POV she is moving sequentially, one place, then another. But from historical time within each world these manifestations have no temporal relationship to each other; only Ciri’s subjective journey links them.

Equally, when she appears in The Witcher world at different times, she is interjecting herself from the mythic sphere that pervades everything that exists in fantasy literature; from the shared mythic lake that stretches across time, cultures and art. Ciri exists in the timeless liminal space between narratives, where world-traveller archetypes lie, but occasionally, when desire – hers or another's – creates precise enough of a key, she flickers into existence in the (historical) time of some particular story.

‘I think that’s the only fragment of the legend that historians have never quibbled about,’ commented the novice, ‘unanimously regarding it as a fabrication and a fairy-tale embellishment, or a delirious metaphor. And painters and illustrators, spiting the scholars, took a liking to the episode. Look, prithee: each picture is Ciri and the unicorn. What do we have here? Ciri and the unicorn on a cliff above a sea beach. And here, if you please: Ciri and the unicorn in a landscape like something from a drug-induced trance, at night, beneath two moons.

‘Ciri and the unicorn emerge from nothingness like apparitions, suspended over some lake or other … And perhaps it’s constantly the same lake, one that spans times and places like a bridge, at once different, but nonetheless the same?’

—Lady of the Lake

The reason artists love it and historians hate it is because artists intuitively grasp that a mythic figure can appear in multiple contradictory stories without paradox. Narratives incorporate the existence of such entities and become transformed through them. Historians, though, require rational explanation, singularity, and empirical verification. Magic is not it. Even human mages, who approach magic as science (as Sapkowski notes in his interview with Bereś), cannot grasp what Ciri possesses: power that unicorns call something other than 'conjuring,' rooted in her elven blood – subcreation through presence.

Ciri can become part of very different legends and it is partly why Avallac’h tells Geralt not to imagine that only his destiny is connected with her. Avallac’h’s entire plot with Ciri involves making her part of another myth, to resurrect and re-embody it.

From Ciri's subjective experience, though, she is searching for home, and in The Witcher it is the moment where Geralt and Yennefer need her. Ciri, the person, is fond of single moments not eternity. Yet she keeps showing up at the wrong coordinates in the archipelago. Each of her appearances is, for her, another failed attempt at finding what she vaguely wishes for but does not wholly know the nature of. It is a series of frustrations, though, from the mythic structure’s viewpoint, all of these manifestations in various historic times occur simultaneously and are as good as all others. By having entered Mythic Time and begun using Elder Blood, Ciri has unknowingly lost her particularity and melded into the endless churn of the mechanism of storytelling; with awareness of it as the minor, bitter reward. She has become archetypal: the Swallow who brings spring, the beginning and the end, a Morgana analogue, that strange, armed lake sprite in some rendition of Arthuriana. Available for manifestation where ever the story-logic demands for her like. In the ‘use’ Plot makes of people lies Ciri’s life’s whole tragedy. Where her individualism dissolves, the possibility of endless beginnings (of something someone wishes for) starts.

The Witcher is a demonstration of its own storytelling.

Ciri’s ability works through genuine desire, because destiny is hope that something we wish for could actually happen, but knowing what to wish for is the hardest thing in the world. Desire brings her near many times. Angoulême's suggestion that the hanza has seen in the snow the footsteps of the Mountain King on an enchanted horse is closer to truth than Geralt knows. Ciri has become a figure from legends intruding temporarily into their historical reality. But without a lighthouse she cannot come full circle. Geralt's Grail Quest requires the Grail’s return, but the witcher’s hands are full while Ciri needs someone to guess at and believe in a particular ending to this story – to guide her to that moment in eternity.

The Ouroboros and ‘the Nimue’

On the wall he was pointing at was a protruding relief portraying an immense, scaly snake. The reptile, curled up in a figure of eight, was sinking its great teeth into its own tail. Ciri had once seen something like it, but couldn’t remember where.

—Lady of the Lake

In Chapter 5 of Lady of the Lake, Ciri cannot remember where she has seen the Ouroboros before. In Chapter 11, it hangs on the Lodge’s wall. In-between, Ciri has exited Mythic Time (or has she?) and a time loop has been closed. Could Ciri have already been at the end of her story and be remembering something that seemingly has not happened yet in linear time?

‘This story,’ she said a moment later, wrapping herself more tightly in the Pictish rug, ‘seems more and more like one without a beginning. Neither am I certain it has finished yet, either. The past – you have to know – has become awfully tangled up with the future. An elf even told me it’s like that snake that catches its own tail in its teeth. That snake, you ought to know, is called Ouroboros. And the fact it bites its own tail means the circle is closed. The past, present and future lurk in every moment of time. Eternity is hidden in every moment of time. Do you understand?’

—Lady of the Lake

The Ouroboros leitmotif, symbolising the connection between cyclical time and the completion of stories, is describing Ciri’s ontological status: she exists in a loop, that is to say, timelessness. She exists in the eternal ‘now’ where everything has always already been written. She has already completed her tale in The Witcher, but she is also still in the middle of it. When she sees the Ouroboros at Auberon’s palace, she experiences anamnesis – not remembering the past but remembering what, in Mythic Time, has already happened and is still happening and will keep happening.

She is remembering either this moment at Tir ná Lia or with the Lodge or another analogue, which, from within historical linear time, has not occurred yet, but from her position as a mythic entity, has always already occurred. In some variation of an archetype, which The Witcher cycle, by ascending among the legends men have told, becomes the moment Sapkowski finishes Lady of the Lake and the first critic reads it.

‘You are at once the beginning and the end,’ says Auberon. Not only metaphorically. A living fable does not die. As a mythical being who transcends historicity, Ciri exists at all points of her story-pattern simultaneously – as a possibility. There are no limits to possibility in Myth. As the Blood of Elves, Ciri embodies Mircea Eliade’s eternal return and the fabled, cyclical mode of being. Returning is perpetual for her for as long as there are people re-telling the tale of The Witcher with all the embellishments of a creative license intact. For as long as anything at all is created on top of and in tune within the set of symbols Andrzej Sapkowski put forth. (Except none of those stories would be the one Pandrzej told.)

While moving in the archipelago of times and places, Ciri is roaming in the amorphous mythosphere, the alternative and pseudo-histories of other places (including Earth). Consequently, she remains perpetually in a state where she could enter her own historical time and complete that story (differently to how it went, too; depending on the lighthouse, i.e. ‘the Nimue’).

As the Child of Destiny, a nexus of plot progression due to how much of the world is tied up with her and to how many Ciri means something, she could return at other moments; the readers like different aspects of the legend, after all. And so we get numerous variations of the myth. In one story-stream she vanishes forever, in another she becomes a goddess, in another she dies. In yet another she saves Geralt and Yennefer and lives happily – that is the tale Ciri recounts to Galahad. All are ‘true’ because in mythic ontology, contradictory narratives coexist without cancelling each other out. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Evidencing her mythic nature, Ciri is all those contradictory stories simultaneously because that is what legends are.

‘Search for her,’ said Nimue. ‘She is somewhere among the stars, among the moonlight. Among the places. She is there. She is awaiting help. Let’s help her, Condwiramurs.’

—Lady of the Lake

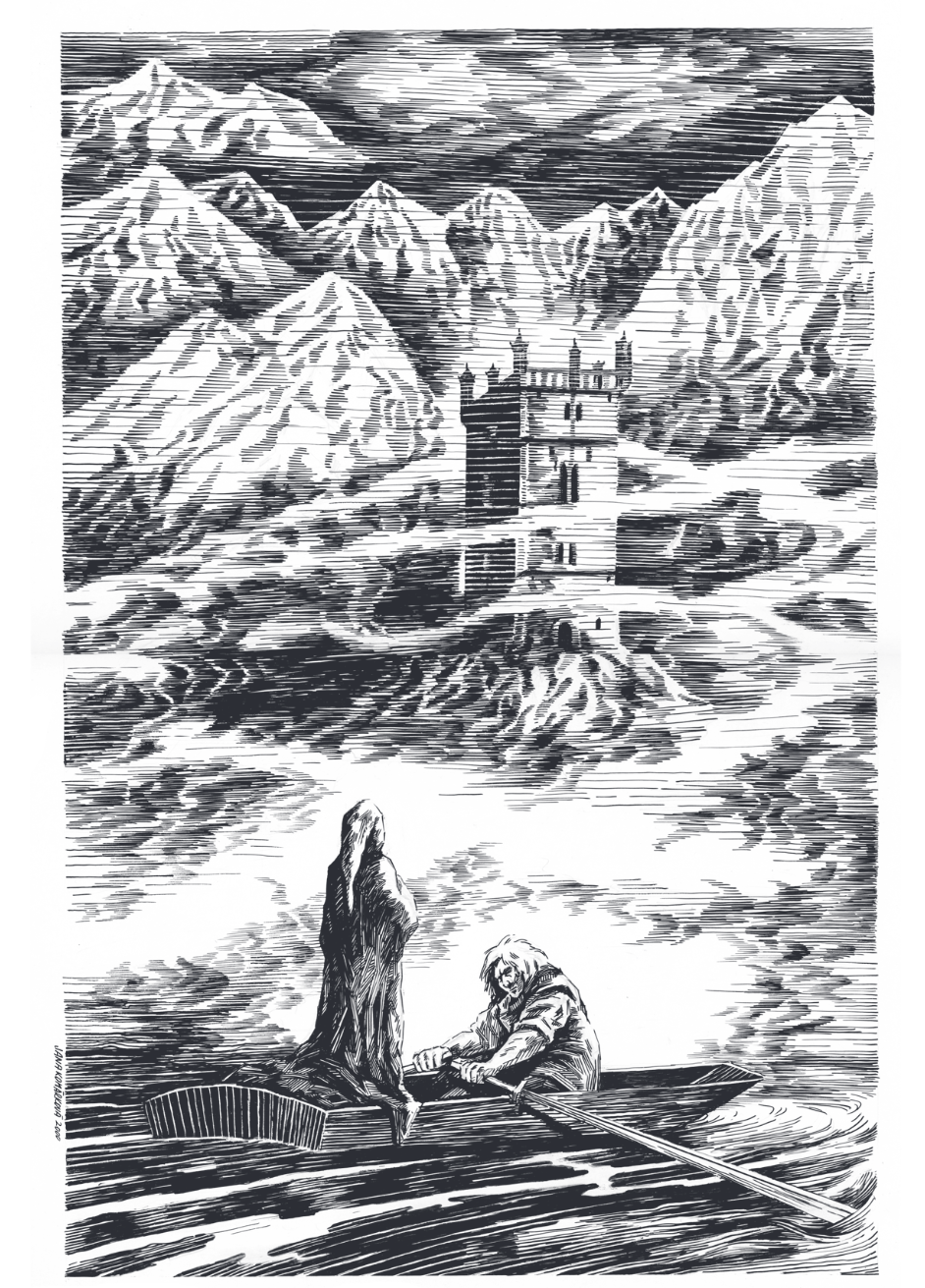

We see that Nimue does not ‘send Ciri back in time.’ Nimue provides, according to her understanding, the narratively correct moment where Ciri’s return is necessary to close the history tying her to Geralt and Yennefer.

‘And you too,’ he said, not looking at her at all, ‘are at once the beginning and the end. And because we are discussing destiny, know that it is precisely your destiny. To be the beginning and the end. Do you understand?’

—Lady of the Lake

The legend’s biggest fan – ‘possessed by a literally pathological obsession’ – raises a lighthouse with with her desire, belief, and study. And not out of nowhere, no. The narrative necessity inherent in Yennefer’s and Geralt’s shared need for what Ciri represents to them demands Ciri return. It is her destiny. The archetypal logic of this legend’s structure (the Grail Quest) demands it. The same force we see in the short story Maladie.

‘Branwen! We’re alive!’

‘Are you certain? Where did we come from on this shore, simultaneously, you and I? Do you remember? Doesn’t it seem possible to you that we were brought here by a boat without a rudder? The same one that once drove Tristan to the mouth of the Liffey? A boat emerging from the mists from Avalon, a boat smelling of apples? A boat we were told to board, because the legend cannot end without us, without our participation? Because it’s precisely we, no one else, who must end this legend? And when we end it, we’ll return to the shore, and the board without a rudder will be waiting for us there, and we’ll have to board it and sail away, dissolve into the mist?’

—Maladie

We can feel it as readers, the necessity that draws the ever-spiralling fairy tale toward a close. One close. One end. And Nimue as an analogue of us helps close the circle in a way that fulfils Geralt and Yennefer’s story’s thematic and structural logic: their Child of Destiny arriving at the destined moment. Because they who must depart must depart with ceremony, with ritual; in the presence of a living myth in the shape of Ciri and the unicorn.

Writing and reading are two sides of the same coin. The story is not finished until it has been read, heard, felt; that’s when it starts living a life of its own. Ciri, a girl become a mythic figure, needs to find a Nimue, a reader, to show her the way out of eternity. It’s the perceiver of a necessity who opens the way. As Geralt looks for the Grail, we look for it side by side with him through the tale we witness and recognize. This speaks to me. This I would have. ‘Everyone must find their own path. […] There are many of them. Infinitely many.’ But from the moment of conception in the author’s mind, the circle was always already closed – a myth exists always in the eternal Now.

Let us not forget though, that Ciri’s own story is ultimately left open-ended: she rides off with a Galahad, back into mythic circulation. Now as then, without Andrzej Sapkowski’s lighthouse but in the imagination of the readers, the witcher girl is still navigating the archipelago. Before Ciri is, indeed, everything. Or as the author puts it at the end of The World of King Arthur: ‘The legend lives on. The Grail is still to be found. Avalon still exists. But it is still shrouded in mist.’