Sapkowski the Pagan - The Grail and the Goddess

Andrzej Sapkowski wrote Ciri as the Holy Grail. Drawing from Celtic mythology and Arthurian scholarship, The Witcher and The Hussite Trilogy explore the Triple Goddess, Wiccan theology, female sovereignty, and love as the Grail's power. The Grail is a Woman.

I noticed long ago that you are quite distrustful towards all experiences of a religious nature.

Yes. Even the term "agnostic" is too weak in relation to me. My worldview is not agnosticism, atheism, or secularism. It is pure paganism. Truly, I am a pagan, and that in the textbook sense of the word. I reject all mysticism, have no idols, and don't believe that I will face punishment for any sins, or that by abstaining from them, I will go to heaven. What's worse, I am deeply convinced that when I die, my body thrown into the neighborhood dumpster will mean just as much as if it lay on a catafalque in the Gniezno Cathedral. After the cessation of biological functions, I will be worth as much as a dog's carcass. I live quite well with this thought.

—Andrzej Sapkowski and Stanisław Bereś. 2005. Historia i fantastyka

One of the more compelling experiences in reading Andrzej Sapkowski is tracking the through-lines permeating his works. It enriches the interpretation of the text; text that is already hermeneutic through his inquiries into the scholarship on the legend of Arthur. To that end, I will be looking at The Witcher, The Hussite Trilogy, and The World of King Arthur. We will see what we’ll find about the Grail and the Goddess. And love.

Naturally, The Trilogy and The Witcher remain separate universes – the author has expressed nothing should be uncritically transferred to the context of the Trilogy – but there are several ideas that repeat in various shapes throughout the author's journey. The lay lines permeating both The Witcher and The Trilogy:

- humanism, i.e. decency

- love’s salving & dooming qualities

- Amantes amentes. Those who love are out of their minds.

- Take heart. Have pity.

- Woman, the Grail

- fairy tales brought to life (but there’s a snag)

- prophecies and grand narratives

- folk stories and beliefs

- witchcraft

- the Cult of the Goddess, the Great Mother, The One who is Three

- the perishing of the old (while an echo lingers) & the brutal onset of the new; change and upheaval

- common sense vs idealism vs pragmatism

- anti-taxes, anti-clergy

- anti-fanaticism

Recommended reading: Weston, Campbell, Eliade, Graves, Wolfram & Chrétien, Jung, Neumann, Parnicki, Bradley, Eliot.

The Grail & The Goddess

“For the Goddess has many names. And still more faces.”

First, Andrzej Sapkowski construing Ciri as The Holy Grail is documented; it is not mere conjecture, although the text overwhelmingly declares it.

Ciri is a central figure in "Blood of Elves" (Krew elfów) and "Time of Contempt" (Czas pogardy). Her story overturns Geralt's life. The Witcher's obsession with this girl, the desire to make her like them by developing and studying magical powers, could it be a reflection of the Witcher's desire for fatherhood, given the sterility of monster hunters due to the potions and poisons they take?

Obviously, that is the one and only reason I introduced the character of Ciri into the story. The plot is based on a universally known fairy tale, according to which a monster (or a sorcerer) saves someone's life and then demands something in return: "You will give me something you find at home unexpectedly." This is the basis of the story "A Question of Price" (Kwestia ceny), and then also "Sword of Destiny" (Miecz przeznaczenia) and ultimately the entire saga.

A girl promised by fate and destiny, the adopted daughter of a sterile witcher and an equally sterile sorceress who changes both their lives, becomes a "damsel in distress," must be found (like the Grail) and saved... a valid story, don't you think?

—Cutali, D. 2015. Interview with Andrzej Sapkowski

But so what?

The Witcher is an incredibly allusive and meta-literary work. Deconstructing fantasy canon and mythical matter, it also meditates on the epistemics of stories and plays out its own ascendancy from historical time into the eternal present of legends. It completes itself as a self-aware analogue of others of its kind, because everything has already been written about. Ciri – Cirilla Fiona Elen Riannon – sits at the centre of its method and madness; not only the axis of the plot but also the spindle of its meta text. It is already evident in her name. O Elaine, O Rhiannon. All Christian legends have a pagan origin. The Polish newborn has pan-European, including Arthurian, origins. Arthurian itself…?

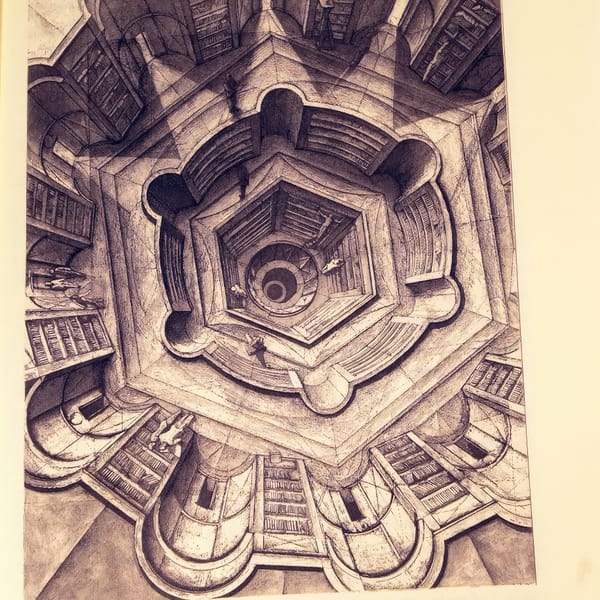

In The World of King Arthur, Sapkowski comments on Arthuriana’s transformation through centuries of re-writes. It is obvious to him that for anyone to understand anything at all about Arthur, they would need to grasp the history of the British Isles and various Celtic mythologies.[1] Arthur was, in all probability, a Celt. And so was the Grail, if not even more ancient. ‘The Grail – like almost every element of the Arthurian legend – has its origins in Celtic mythology. This is absolutely certain and has been confirmed many times,’ he writes in Świat króla Artura. So what did Arthur believe? What views and values did the world from which he emerged possess? Why is this relevant to a more meaningful reading of The Witcher?

The world of the Celts, as so many pre-Christian cosmologies, was a living world – an animistic, self-eating and self-renewing entity. Cyclical, circular, without beginning or end, embracing life out of death – and so with Ciri, who is a living Grail.

A living Grail. A girl. A young woman. A Goddess. She who is Triple. A source of rebirth and hope, and of death too. Strange magic is enclosed in her veins, as in Ceriddwen’s Cauldron, that is of the essence of life. Cauldrons abound in Celtic mythos (Dagda, Cuchulainn, Brân or Pwyll – all got their hands on a cauldron eventually). But Ciri does not need to be rendered an artefact in order to hold power, because… she is a woman. That alone is enough.

Yennefer, Calanthe, Meave, Milva, Nenneke, Angoulême – Sapkowski consistently writes compelling female characters, but he does not advocate for matriarchy.

For me, the marginalization of either sex is pathological. Just as I am convinced that the role assigned to women in the nineteenth century can not be considered a norm, I also consider it unhealthy to reverse the situation, in which women dominate over men. Equality does not mean that one sex is superior over the other. […] In my work, however, I try to show that a woman really dominates in nature, but not because of her social role, but only because of the organism that nature has endowed her with. Any doctor will tell you that women are more resistant to pain, are less likely to succumb to any infections and diseases, and have greater regenerative abilities. Man is a much weaker creature in nature.

—Andrzej Sapkowski and Stanisław Bereś. 2005. Historia i fantastyka

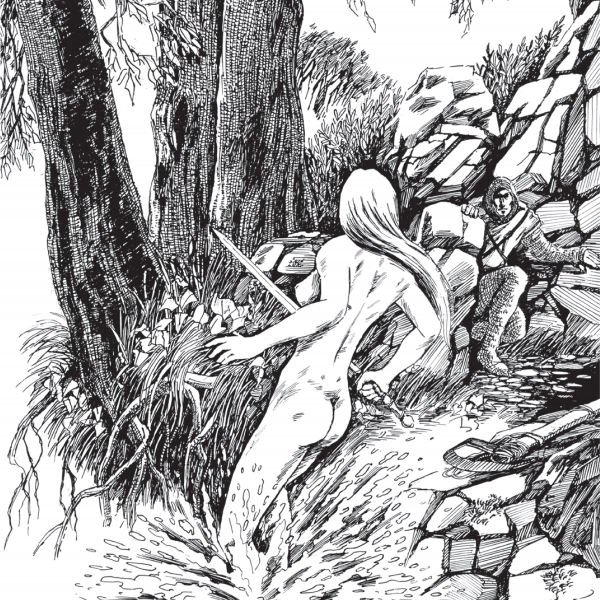

The author works from some accounts of Celtic beliefs according to which female sovereignty was bestowed great symbolic significance. Earth was feminine and the Queen its icon, just as the King was associated with the Sky (and fertilizing rain). This explains the prevalence of aitheds, stories of the abduction of women, which from male perspective amounted to both love stories and quests for legitimacy and power. It remains important, however, that the man who ‘gets’ the woman be worthy – the competition is a test. Therefore the narrative judgement in The Witcher favours someone like Geralt, who transforms in search of and in the name of the women he holds dear, and condemns the likes of Vilgefortz who try to usurp and control nature, dehumanizing and dominating the Female Other. The Queen is not to be dominated. Her assent matters. In this sense, Andrzej Sapkowski remains a romantic.

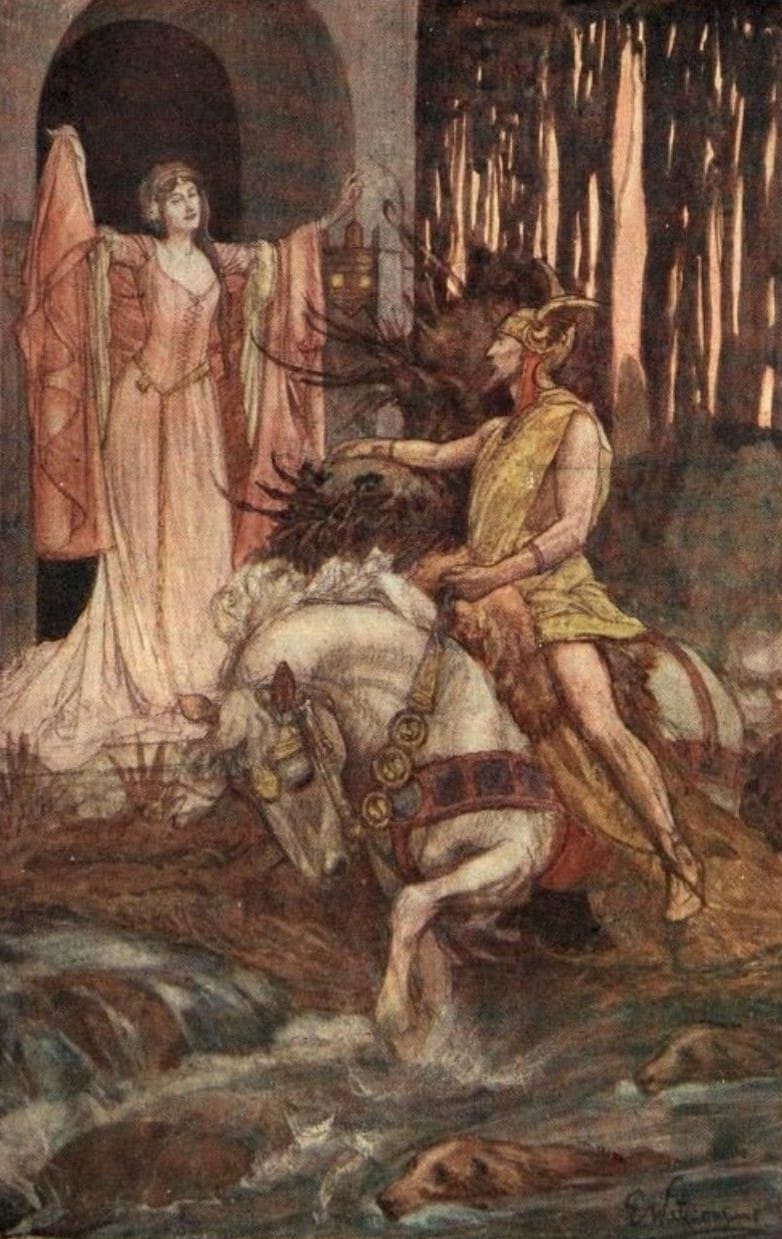

It was from these versions that Guinevere and Isolde were born – and the attitude that the authors of subsequent versions of the myth have towards these characters. Both queens betray their husbands. This is very ugly… but somehow we like them. And we justify… Well, Guinevere wasn’t a faithful wife – but she was a faithful lover (trew lover).

Why do we like Guinevere and Isolde? Is it not because both of these characters resound with Celtic echoes, echoes that are close and pleasant to us, people of the emancipated twentieth century, who (not all, not all) are repulsed by male chauvinism and gender discrimination in every respect? For among the Celts, a woman – and especially a queen – had full rights and enjoyed the same privileges as a man. There could be no question of any discrimination. Like a male king, the Celtic queen could, if she chose, be promiscuous. If the king could unscrupulously take concubines to bed and not be universally condemned for it, then no one could forbid the Celtic queen from having lovers on a one-night basis. The queen personified the Great Goddess, and the goddess’s actions are not questioned. The famous Boudicca’s preferences in bed were known, and the erotic exploits of the equally famous Catrimandua, queen of the Brigantes, became almost legendary. About the mythical Medb, Queen of Connachta, wife of King Ailill, Irish legend tells us that she often and without hesitation gave handsome men the “friendship of her thighs.”

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

'Celtic mythology,’ Sapkowski notes, 'is mainly about the love life of the gods.’ Gods fighting, scheming and transcending themselves for goddesses. It’s called the oldest story in the world; girl meets boy. But that’s not quite the beginning of it: in the beginning, we are all born to a mother.

The Grail’s functions and characteristics are notably maternal and feminine, and the mystery and nature of the Grail’s power is love.

“You will become stronger, you will become the bravest among the brave, because The Grail is a source of power and courage, and the Grail of Grails is my femininity.”

There is only Beatrice. And she just isn’t there. Enigma. Mystery. All the love literature in the world.

The grail is a woman. But the words used by Teodor Parnicki are not spoken by a woman. They are spoken by the Goddess.

For, as Marion Zimmer Bradley says in the Mists of Avalon, the gods are many and they have many names. But there is only one Goddess. Great, White, Triple. The one who was, is and will be.

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

Great, White, Triple

Who is She? What is She like?

The ability to provide food is the property of the Grail most often referred to. Nourishment. Revitalization. Mother is the only parent who may truly feed her child with her body. Or give birth. The Chalice symbolically representing the ‘Womb of the Mother’ is a very old idea. Old and basic. The most basic. Bernard of Clairvaux even calls upon Mary, saying: ‘Offer your son, sacred Virgin, and present the blessed fruit of your womb to God. Offer the blessed host, pleasing to God, for the reconciliation of us all’ (qtd. in Bynum, 268). But we’ll talk about the role of Christianity and symbolism another time. First, we are pagans.

Drawing from various sources, I assumed that – although I am not a blind follower of this theory – the feminine element dominates in nature. If there is any cult not related to politics, it is the cult of the Great Mother, the Goddess. The belief in the male God, Yahweh, worshiped by Jews, had a political character – Yahweh was invented because he had to be invented to maintain certain social structures. For primitive people, the mysterious, divine element was exclusively femininity, the ability to give life. However, I emphasize that I am not defending these theories from a religious studies standpoint; they simply resonate with me.

—Andrzej Sapkowski and Stanisław Bereś. 2005. Historia i fantastyka

This idea that resonates with the author so strongly as to appear in virtually everything he has written was re-kindled as an ideology by the neo-Celtic, neo-pagan Wicca movement (Gardner, Murray, Starhawk, et al). Foundational text: The White Goddess by Robert Graves. The idea precedes the Celts though, and, at heart, revolves around nature and man being inseparable.

Ceridwen is one of the forms of the Celtic Goddess, and her cauldron is the womb-cauldron of rebirth and inspiration. In early Celtic myth, the cauldron of the Goddess restored slain warriors to life. It was stolen away to the Underworld, and the heroes who warred for its return were the originals of King Arthur and his Knights, who quested for its later incarnation, the Holy Grail. The Celtic afterworld is called the Land of Youth, and the secret that opens its door is found in the cauldron: The secret of immortality lies in seeing death as an integral part of the cycle of life. Nothing is ever lost from the universe: Rebirth can be seen in life itself, where every ending brings a new beginning.

Most Witches do believe in some form of reincarnation. This is not so much a doctrine as a gut feeling growing out of a world view that sees all events as continuing processes. Death is seen as a point on an ever-turning wheel, not as a final end. We are continually renewed and reborn whenever we drink fully and fearlessly from “the cup of wine of life.”

—Starhawk. 1979. The Spiral Dance

Nature’s heartbeat resounds in reincarnation through reproduction. The gentle fury of love.

“Listen to the words of the Goddess, whose arms and thighs are wrapped around the Universe!” called the shaman. “Who, at the Beginning, divided the Waters from the Heavens and danced on them! From whose dance the wind was born, and from the wind the breath of life!”

“I am the beauty of the green earth,” said the Domina, and her voice was like the wind from the mountains. “I am the white moon among a thousand stars, I am the secret of the waters. Come to me, for I am the spirit of nature. All things arise from me and all must return to me, before my visage, beloved by the gods and mortals.”

“Eiaaa!”

“I am Lilith, I am the first of the first, I am Astarte, Cybele, Hecate, I am Rigatona, Epona, Rhiannon, the Night Mare, the lover of the gale. Black are my wings, my feet are swifter than the wind, my hands sweeter than the morning dew. The lion knows not when I tread, the beast of the field and forest cannot comprehend my ways. For verily do I tell you: I am the Secret, I am Understanding and Knowledge.”

"Worship me deep in your hearts and in the joy of the rite, make sacrifices of the act of love and bliss, because such sacrifices are dear to me. For I am the unsullied virgin and I am the lover of gods and demons, burning with desire. And verily do I say: as I was with you from the beginning, so you shall find me at the end."

—Sapkowski, A. 2002. The Tower of Fools

It is for this reason the Irish recorded so many songs of aitheds - motifs of female abduction. It is for this reason one of the earliest legends of the search of the Grail is the tale of the hero Culhwch’s quest for the hand of Olwen, who, wherever she stepped, made four white clovers bloom under her feet.[2] It is why Ciri, the living Grail in whom the function of the Goddess has been doubled, finds herself in a double-bind; as the keeper of power and immortality she is more frequently seen as means to an end rather than an end in herself. Not unusual for any failed relationship where the parties confuse love for something else. And while we are confusing notions of erotic and spiritual love, the Question of the Grail which must be asked of the Fisher King, undoubtedly, still comes down to a question about love.

Two men compete for a woman. Finn-Gráinne-Diarmuid, Conchobar-Deirdre-Naoisi, Eochaid-Étaín-Mider, Pwyll-Rhiannon-Gwawl, Lleu-Blodeuwedd-Goronwy, Arthur-Guinevere-Lancelot, Mark-Isolde-Tristan. In this arrangement, there is a reference to the cycle of nature - the seasons. The young hero symbolizes summer, rebirth, the surge and flowering of vital forces, which he contrasts with the winter, dying strength of the old king. And the ruler cannot be weak, he cannot be sterile or cold or sexually ineffective - after all, he is married to the Earth, the Great Mother, symbolized by the spring queen, who during the Beltaine mystery has to be loved - loved physically, erotically. The sexual failure of the spouse of the Goddess is unthinkable - it could bring about the infertility of the Earth and the devastation of the country.

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

Celtic mythology is about the love life of the gods. The longing for a union; that completes. That turns the wheel and closes the cycle. That revitalizes, heals, nourishes, allows for flourishing. That immortalizes; if not oneself, then at least the moment. And what is life but fleeting moments, grains of sand passing through an hourglass?

"What is the Grail?"

"Something you are looking for [...] Something that is most important. Something without which life loses meaning. Something without which you are incomplete, unfinished, imperfect." [...]

"All evening [...] you sat next to your Grail, idiot."

—Sapkowski, A. Something Ends, Something Begins

It can get confusing. The Goddess has many names and many faces, and three aspects.

There are many gods and they have many names. But there is only one Goddess. The one whose images were carved on the walls of the cave, whose figurines were carved from mammoth tusks not two thousand, but twenty-five thousand years before the birth of Christ.

She who is Triple is the Virgin, the Pregnant Mother and the Crone - Death.

The one who emerged from Chaos before Time even existed. She who separated the Waters from the Heavens and danced on them, and from her strokes the wind was born – and the world began to breathe [...] The giver of life and the one who takes life – so that it can be created again. The Great White Goddess, who was later given many names: Mut, Anat, Ishtar, Tiamat, Astarte, Inanna, Cybele, Isis, Shakti, Gaia, Artemis, Terra Mater, Bona Dea, Minerva, Diana, Lilith, Danu, Dôn, Arduina, Epona, Ceriddwen, Arianrod, Morrigan [...] The one whose priestess was Mary of Magdala, later called Magdalena [...] The one for whom people danced before the bulls in Crete, for whom menhirs and cromlechs were erected [...] For whom Stonehenge, Avebury, and the tumuli of Brugh na Boinne were built. The one whom the Celts worshiped in the form of matrons. The one whose image was on Arthur's shield at the Battle of Badon.

The one that was, is and will be.

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

As to the inherent eroticism of the Grail, well…

I won't say a word more.

Well, maybe just one more: the basic Wiccan cult objects, without which no Wiccan mystery in honor of the Great Trinity can take place, are the cup and the sword.

The Grail and Excalibur. The rest is silence.

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

He wanted to tell her everything, but the words stuck in his tight throat.

She saw it. She knew. How could she not? For only in Reynevan’s eyes, stupefied by happiness, was she a maiden, a trembling virgin who was embracing him, eyes closed and biting her lower lip in painful ecstasy. For any wise man – had there been one nearby – the matter was clear: she was no shy and inexperienced young lass, but rather a goddess proudly receiving the homage due to her. And goddesses know and see everything.

And do not expect homage in the form of words.

She pulled him onto her and the eternal rite began.

—Sapkowski, A. 2002. The Tower of Fools

The author’s interest in the fates of men in the power of the Goddess is only surpassed by his hope for the triumph of common sense and humanism. And the mystery of the Grail – what unleashes its power? – is of both sexual and platonic variety. Humanity is important. Heart. As in Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. As per Campbell: 'The big moment in the medieval myth is the awakening of the heart to compassion, the transformation of passion into compassion. That is the whole problem of the Grail stories, compassion for the wounded king.’[3]

Thanks to Ciri, the story of Geralt of Rivia – a grail knight who set out with his hanza in search of a dream – is ennobled and raised on par with King Arthur. It is Yennefer and Geralt’s love and compassion and sacrifice for Ciri, which ultimately heals them. An echo of love for his daughter melts the ice shard in the heart of an Emperor. The mystery and nature of the Grail’s power resides in love.

“Love has many names,” said Hans Mein Igel suddenly, “and it will determine your fate, young herbalist. Love. It will save your life when you won’t even know that it is love. For the Goddess has many names. And still more faces.”

—Sapkowski, A. 2002. The Tower of Fools

By the end of The Witcher, Ciri’s journey as the Goddess has barely begun. And what has begun has begun traumatically. Her journey to know herself, to find, forgive, understand, and accept (or reject) the Grail within, has not yet dawned. She remains in a liminal space between the Maiden and the Woman after having, already, and much too early, worn the guise of Death the Crone. The author doesn’t tell; he lets the reader wonder. For before Ciri is everything. But the Grail, the Goddess, requires something, and also empowers with what she requires.

He cautiously assisted her, still more cautiously overcoming her instinctive resistance, her quiet, involuntary trepidation.

Once the cambric chemise was lying atop the other garments on the ground, he gasped, but Nicolette didn’t let him feast his eyes for long. She pressed herself tightly against him, entwining him with her arms and searching for his mouth with hers. He complied. And what his eyes had been refused, he delighted in with his touch, paying homage with trembling fingers and hands.

He knelt down. Bowed at her feet. Worshipped her. Like Percival before the Holy Grail.

—Sapkowski, A. 2002. The Tower of Fools

Love leads spring into the Waste Land of the human heart.

Love, compassion, willingness to suffer with and for another. Readiness to transcend one’s own pain, selfishness, and rage. Because three things last forever: faith, hope, and love – and the greatest of these is love.[4]

I would not like to theorize that the forerunner of the search for the Grail was the hunt for a large wild pig. I don't want to be so trivial. I prefer - following Parnicki and Dante - to identify the Grail with the real goal of the great effort of mythical heroes. I prefer to identify the Grail with Olwen, from whose feet as she walked, white clovers grew. I prefer to identify the Grail with Lydia, whom Parry loved. I like New York in June. . . How about you?

Because I think that the Grail is a woman. To find her and win her, to understand her it is worth sacrificing a lot of time and effort. And that’s the moral.

—Sapkowski, A. 1995. The World of King Arthur

Footnotes

Sapkowski mainly used Mythology by Thomas Bulfinch, Celtic Myth and Legend, Poetry and Romance by Charles Squire and Mabinogion. ↩︎

In order to marry Olwen, Culhwch must take her from her father, but Ysbaddaden will first set him on an endless quest; a list of long and laborious tasks. In the name of a woman. ↩︎

Campbell, J. 1991. The Power of Myth ↩︎

Or as The Tower of the Swallow renders it: ’Are, then, Chaos, art and learning according to you, the Powers capable of changing the world? A curse, a blessing and progress? And aren’t they by any chance Faith? Love? Sacrifice?’ ↩︎