Who is Eredin Bréacc Glas in The Witcher books?

In the Witcher games, Eredin is a template death knight. In game-fanon, he is frequently a BDSM, ultra-top/dom, plotting maniac. In the Witcher books though, Eredin is a reckless but loyal servant of the Aen Elle, disillusioned, haunted by the prospect of failure, and resolved to do what’s needed.

‘Among the elves,’ the sorceress whispered pensively, ‘there is a legend about a Winter Queen who travels the land during snow-storms in a sleigh drawn by white horses. As she rides, she casts hard, sharp, tiny shards of ice around her, and woe betide anyone whose eye or heart is pierced by one of them. That person is then lost. No longer will anything gladden them; they find anything that doesn’t have the whiteness of snow ugly, obnoxious, repugnant. They will not find peace, will abandon everything, and will set off after the Queen, in pursuit of their dream and love. Naturally, they will never find it and will die of longing. Apparently here, in this town, something like that happened in times long gone. It’s a beautiful legend, isn’t it?’

—Yennefer of Vengeberg, A Shard of Ice

Eredin Bréacc Glas is an Aen Elle warlord in charge of Dearg Ruadhri – the Red Riders – who retain the ability to break through the barrier between certain worlds post-Conjunction. During nights of magic when the veil between the worlds is thinner, a spectral elven cavalcade goes around the Spiral, earning itself notoriety among the inhabitants of the Continent as the Wild Hunt. The Aen Seidhe are likely to know about the Hunt’s true nature in lieu of a tale about the Winter Queen, while the majority of the populace regards the Dearg Ruadhri as demons – phantoms from hell.

This practice of beautification and mythicization of Truth forms the crux on which Eredin Bréacc Glas’s character turns: the power we hold over others by means of truth pales in contrast to holding captive their imagination.

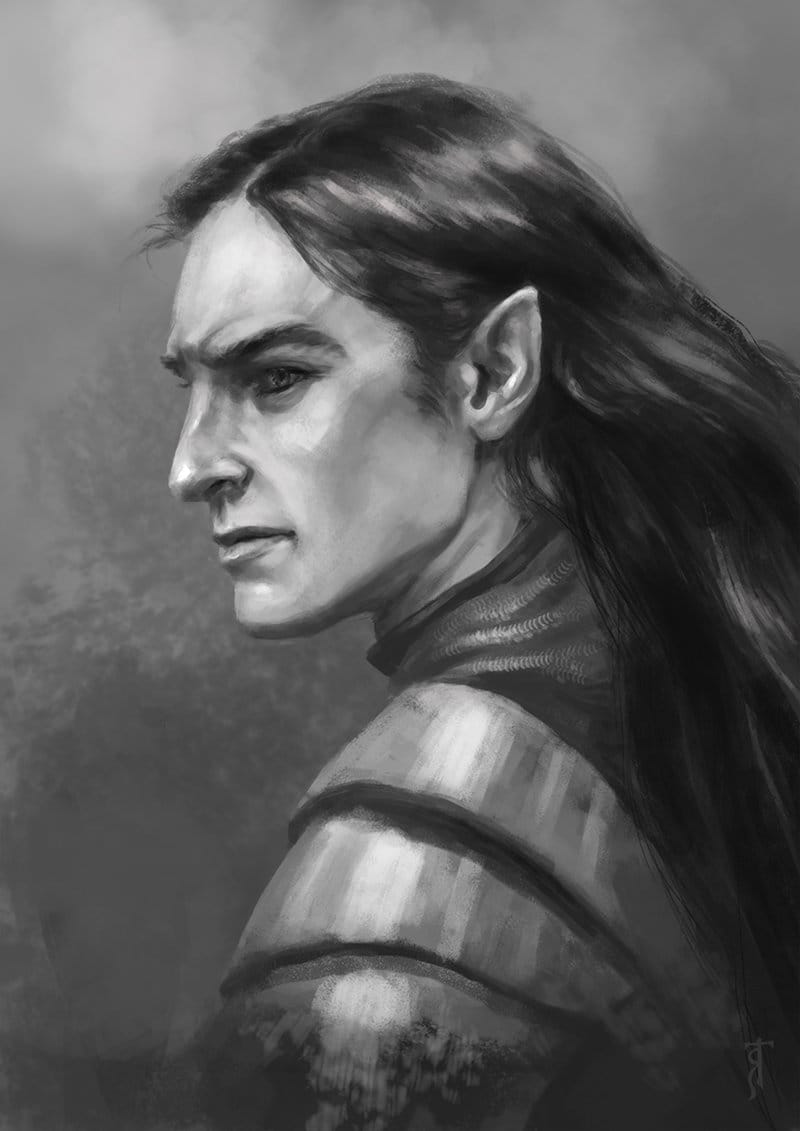

Canvas for Fantasy

The reader witnesses Eredin first and solely through the eyes of a 16-year old girl. Every time he appears, he inhabits a role; steps in as a canvas for a fantasy. Be the role that of a mythical skeleton-wraith, a war hound sent by the Ruler of the Otherworld to retrieve the elves’ long-lost, prized possession. Be it the role of a border patrol, a rude and impatient horse lord doubling as a not-so-nice jailor and partner-in-crime to another ‘nice’ elf. Be it a scheming pretender to the throne.

Roles.

On his on, Eredin is a black box. Comparatively thinly-sketched, he is given no backstory. Andrzej Sapkowski did not tie him closely with the drama surrounding Ciri’s lineage other than making Eredin an inversion of Cahir in a story template that repeats itself between worlds – a Knight to a Ruler who seeks Cirilla Fione Elen Riannon on the agitation of a Wizard. The Continent and the elven Otherworld mirror each other in a twist. Aside this, however, Eredin remains essentially a stranger both to Ciri and to the narrative at large. A stranger who does not explain himself.

In fact, nothing at Tir ná Lia explains itself; the author goes as far as to make Ciri insist on not wanting explanations to anything. It makes it so that everything the reader witnesses in Faërie filters through the incomplete frame of a trauma-fleeing teenager, who is being purposefully kept in the dark besides. Ciri is not a reliable narrator, but she does not stop trying to make sense of things. It is her imagination that fills in the blanks. This matters, because appearances deceive – such is the narrative arc with these elves.

By making the reader’s central point of view unreliable in a context that intentionally seeks to confound and lead the reader astray, commentary is passed on the power of illusions. This is a theme that repeats itself throughout Lady of the Lake. It also explains how A. Sapkowski writes (and does not write) Eredin Bréacc Glas. Like a mirror that shows you only what you show it, Eredin shines back the confusion and fantasy of a young girl (and the reader) who put it there.

Wait, but does Eredin not covet the throne of the Alder King? Isn’t that his hidden motivation?

What would you say if I put to you that no, it is not? At least not in the way CD Projekt Red chose to interpret it in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. In the books, Eredin is driven by a dream of power achieved by way of regaining control of the Ard Gaeth. Nowhere but in Ciri’s imagination does the text allude to his having designs on the tor’ch. The truth of Auberon’s demise is left open to interpretation – all the more power to the reader! – but in the strictest reading, the best the prosecution can lay on the warlord is accidental manslaughter. Which lacks the intentionality of an ‘ambitious pretender’ required for moulding a sparely rendered character’s entire characterisation around itself – as has happened in fanon canon after The Witcher 3 released.

The illusory nature of Truth is central to Ciri’s journey in Tir ná Lia; the interpretations she makes are valuable. Just not necessarily true as maps.

Narrative Purpose

Eredin’s function starts showing in the deceptive, mythicized nature of the Hunt, which compels in reality and in the Witcher Saga for similar psychological reasons. Humanity is tempted to believe in the existence of justice in the universe, and the Wild Hunt looms large in our imagination because it acts out a scenario people on some level suspect they deserve. Justice for our deeds, for our nature. In case of the Hunt though, what does this justice translate into? Wild abandonment. Or hell and punishment.

Both impulses – seeking divine permission for violence or awaiting cosmic retribution – demand the same surrender: humanity abdicates individual moral responsibility and collective possession fills the void. An inexplicable, collective madness, as Geralt puts it. In the worst nature of man, he seeks licence to pursue his desires with impunity (in which case the Hunt is the harbinger of war), but also fears the consequences (in which case the Hunt abducts the wicked). It is, indeed, madness to pursue large-scale destruction of your fellow man, so man relinquishes his will and becomes a demon in the war horde on its mad path. His wicked soul is ‘reaped’ by the Wild Hunt and taken into a personal hell, a nether-realm of the Self.

(Despite their wonders, Otherworlds were never safe places for mortals – they served as sites of transformation, of coming to know yourself. An Abrahamic religion, which equated them with Hell, simply capitalised on a common indigenous wariness, as did Sapkowski and many other fantasy authors.)

Divested of mythical drapes and theatrics though, Eredin and the Dearg Ruadhri act as raiders while off-world – capturing slaves, probably bringing in treasure, precious resources and species from across the Spiral. Bringing knowledge! Indeed, they might even act as traders in the vein of Norsemen. And in the world of the Alders, the Red Riders patrol the plains, guarding the realm of elves against unicorns and threats implied to exist in the wilds beyond the elves’ barriers. Their function, as opposed to display, is prosaic. Upon meeting Ciri on her way to Tir ná Lia, Eredin, inversely to a demon dragging a human into hell, presents as a protector helping a maiden get into paradise. As it happens though, he and the Dearg Ruadhri also ensure nobody leaves paradise.

The question of what is an illusion and what is reality starts here.

Ciri (and the reader) becomes aware of Eredin’s existence as a result of being saved from charging unicorn herds. An elven knight appears, as if by coincidence, offering his aid in a moment of need. In truth, the help is not altruistic. In truth, an extraterrestrial hunter has come to scrutinize the ‘catch’ that eluded him on the Continent; whom he shielded against vultures on Tarn Mira so she might fly into the hands of a fellow predator. In truth, Ciri and the reader have already met Eredin Bréacc Glas several times – as a Wild Hunt wraith – but Ciri and the reader do not know any of this just yet.

‘I told you that you were mine!’ roared Bonhart, spurring on his bay. ‘That I’ll do what I want with you! That no one will stop me from doing it! Not people, not gods, not devils, nor demons! Or enchanted towers! You’re mine, witcher girl!’

An armed man with a crown on his helmet and a necklace bumping against the rusty cuirass on his chest, galloped at the head of the demonic cavalcade.

Begone, rumbled a voice in Bonhart’s head. Begone, mortal. She is not yours. She is ours. Begone!

An imposing black-haired elf in a mail shirt appears, riding a dark bay stallion as huge as a dragon. The horse wears a demonic horned bucranium and its master’s facial features bring to mind a bird of prey – black, dark, evil. Even his toothy smile looks ghastly somehow. Such are Ciri’s initial impressions. They contrast starkly with her first impressions of Avallac’h and the world of elves: after exiting the Tower of the Swallow, Ciri is convincing herself she is not at all astonished by the beauty, or by the very possibility of it, in the world of the Alders where everything – in Ciri’s mind – must be different. Except Eredin is familiar. Like an echo of the brutal, ugly world of violence Ciri has known up until now. Ciri’s impressions are the first narrative lead toward an impending mask-break.

The narrative makes Eredin flirt with breaking the fourth wall of his ‘role’ at Tir ná Lia pretty much constantly. He is the flashy buoy indicating ‘something is rotten in the state of Denmark.’ Does Ciri not notice? She notices. She views Tir ná Lia as a prison after all. The question is: does she believe it? Would Ciri rather believe that by entering the Tower of the Swallow she is getting what she deserves by way of a fairy tale or a nightmare?

In parallel to how Geralt loses himself in Toussaint, Ciri loses herself in the illusions of Tir ná Lia until they shatter, and Eredin Bréacc Glas plays the part of a disabuser who does the shattering. Ciri experiences mask-breaks with Avallac’h and Auberon both. Not so with Eredin. Avallac’h – the helpful, caring one – comes close to strangling her and Auberon – the unhurried, mature one – throws a violent fit and a litany of insults her way. Eredin – the rude, preying one – stays as he is. He does not fulfil Ciri’s fantasies, but he does not break his image either. He is as he is. He is the cliff against which Ciri breaks her hopes, realising her error: beautiful looks and profound intentions do not eliminate prosaic realities. Eredin is the prosaic reality. At the same time, what Eredin is really about in private and in his own right remains unknown. For narrative purposes, it matters more to show that Ciri cannot pin her hopes on anything she does not really understand, and that by seeking to understand (to be more elf-like, to try with Auberon, empathise with Avallac’h, and use Eredin’s nephrite flacon) she enmeshes herself in a game the rules of which she does not determine, and loses herself.

The narrative turning point occurs after the Bower Scene. Until then, everything goes. Until then, Ciri spirals steadily toward apathetic submission. The first crack appears at the discovery that all servants in paradise – mute and meek – are human, like her. The second one as Eredin tries to intervene in the deadlock concerning the Alder King’s bedchamber. Third and final nail in the coffin comes when Auberon loses his temper, threatens Ciri with Avallac’h’s laboratory, and shows the girl the present moment in Ciri’s home-world in which Yennefer has drowned in the bottom of the lake and Geralt has frozen to death. Eredin had warned her, but she had not wanted to believe it.

That Eredin conceals the elves’ twisted nature through Ciri’s own self-delusion becomes clear only later because the warlord, personally, is one of Ciri’s fantasies. He appears as someone Ciri on some level suspects she deserves even in a fairy tale where everything is supposed to be different. Eredin holds up the unwanted mirror to the ugliness in Ciri, while also slotting into the template of a knight in shining armour. (Someone to put her on the throne? Someone who could help her reclaim her legacy, as she wished to do by setting her sights on Tor Zireael?) Fairy tales. The kind someone with a damaged sense of self-worth might have.

Ciri is not being let in on the real score and it is easy enough, because Ciri is busy trying to stick to the plot. She is busy trying to present herself as graceful, proud, to be taken seriously. Someone who has more elf in her than she realizes. Someone for whom an entire troop should ride up – a little different from ‘a golden carriage and six and a retinue of courtiers’ she fashioned for herself as the rightful princess of Cintra, but still. The plot conventions demand it! No wonder then that Eredin’s unimpressed reaction, contrasting so strongly with Avallac’h’s narrative, discombobulates Ciri.

Holding captive the imagination requires perpetuating a combat between what we hope we deserve and what we fear we do.

By the time first impressions conclude, Ciri has had the chance to entertain several ways this plot of becoming a mother to a child with an elf could unfold. Has the groom not ridden up to meet his prospective maiden? No? Well, how about this Wizard’s ‘entitlements’ and her resemblance to his lost love, then? Not to say that the ‘gold nugget in a pile of compost’ is so dreadfully effective precisely because it picks at Ciri’s insecurity – she hopes that she is more than what the base and evil world has been reducing her to, and that her worth might be acknowledged. Hope! And when her worth is acknowledged by someone who sounds equally unlike an ‘elf-ideal’ as Ciri herself, then there is also something perversely comforting about it. Her fascination reaches its peak when the warlord hands her a myrtle flower, because in Ciri’s imagination, Eredin looms large due to how he addresses Ciri’s nature – in a way she believes is truthful to her self image, in contrast to the surrounding paradise she fears she is simply unable to live up to.

It just so happens the paradise is concurrently hell, and Eredin anything but human.

Eredin's Characterisation

Eredin’s personality is relatively straightforward. He is not subtle; neither in words, nor actions. Which is not saying he cannot discern subtleties: he binds insult and compliment elegantly enough, e.g. toward Avallac’h in regard to Ciri’s resemblance to Lara Dorren. He simply bets on shock and awe most of the time, particularly as in his profession he faces problems that require immediate and foolproof solutions. Thus, he is wont to pay attention to the weak links in the net rather than to whether the prey ought to be caught with such a net in the first place.

Eredin’s manner is relatively unadorned; simpler and to the point. Brusque bordering on ungracious, if not downright crass. It does not mean he is unfeeling, nor that he lacks manners; it just might be that he doesn’t deem you worthy of them. There’s a sense of poetic appreciation to the way he considers the life of a butterfly, and he adjusts his behaviour toward politeness frequently: upon apologising for his harsh words; by taking note of being chided for impatience and convincing Auberon to let Ciri freshen up after her journey; by giving due praise to a rider when praise is due.

In short, Eredin is not dumb. He is reckless.

It makes him come off as direct in comparison to his fellow elves, yet this recklessness should not be mistaken for honesty. (Fandom, for some reason, does it often.) Eredin is supremely confident in his abilities and underestimates Ciri, because of which – even while omitting things left and right – he toys with the truth in plain sight, knowing it sounds unbelievable to Ciri. Because Eredin is, above all, perceptive. Like a Sparrowhawk should be. Lest we forget, Eredin is a warlord and a sentry. That’s his task. He acts because his duty is to react. He keeps a neurotically close eye on the Swallow when he can, provoking her for reactions upon which to sketch out his own actions. Ciri’s fascination – and her fantasies – are something he takes note of immediately and works them to his advantage as the person most concerned with not letting her escape. Note, for instance, how he takes the opportunity to test the speed of Ciri’s mare (her prime means of escaping him) while challenging her to a race. Antagonising her gets to her – it is like catnip. Upon being patronised (as per Avallac’h and Auberon) she flusters or breaks down, but upon being challenged directly, her gears start turning and she starts acting – and Eredin, the hunter, is all about preventing action.

Recklessness, however, makes Eredin unwise. He intimidates and provokes (his modus operandi) to the point of stupidity really, which makes him come across as terrified of failure deep down. This fear seems appropriate and commensurate with the way his eyes light up at the notion of hasting to re-gain control of Eternity (the Gate of Time). Eredin frequently acts before he thinks. And speaks too much – nowhere is it clearer than at the moment when he lets it slip to Ciri she has ‘a wild talent,’ which still won’t be enough to overcome him. He does not come off as a long-term strategist, and he is mistrustful to boot – of his prey, of his compatriots, of Destiny and the very ends for which he is nevertheless resolved to do what it takes as long as it leads to the power he dreams of. His eyes shine at the prospect of Eternity and he defers to Avallac’h’s expertise, trying to stick to the plan. Except when the plan seems to grind to a halt, he is quick to look for prompt, efficient means of intervention. Whether or not he knows better. He certainly thinks that he knows better. Because Eredin is reckless and fearful that the end will never come.

‘You ought not to draw a weapon on me, Zireael. It’s too late now. I won’t forgive you that. I won’t kill you, oh, no. But a few weeks in bed, in bandages, will certainly do you good.

‘Wait. First, I want to tell you something. Disclose a certain secret.’

‘And what could you tell me?’ he snorted. ‘What can you tell me that I don’t know? What truth can you reveal to me?’

‘That you won’t fit under the bridge.’

He also has a vengeful streak, though pride is a common denominator of all elves.

Motivation – Books vs Games

Ironically, the most significant difference between the books and the games concerns Eredin’s loyalty.

In The Witcher games, Eredin is at first a scary framing and exposition device, then framing device++ (The Witcher 2 has him the most book-like he gets), and finally a filler for every death-knight fantasy ever, devoid of personality and a cackling regicide to boot. It is the unfortunate service of the last, most successful game – that saw many re-writes and cuts – that Eredin is being deemed a megalomaniacal usurper; that he desires the tor’ch more than regaining control of the Ard Gaeth.

Frankly, I think this is just incorrect.

In the books, Eredin is loyal to the Alder Folk’s cause. He may mistrust Avallac’h’s methods in pulling the strings of Fate, but he is not shown to be at odds with either Avallac’h or Auberon over the end result, which is so-so much more impactful if achieved than becoming another trapped Alder King on the Spiral, a living corpse with the tor’ch eating into the skin of his neck. Unicorns deem Avallac’h and Eredin their prime antagonists now, but they name them along Auberon; for narrative and symbolic purposes, the three act together as a Triad. Eredin himself, when chasing Ciri, places emphasis in a revealing manner: ‘You can’t not know that you’re only delaying the inevitable. You belong to us and we’ll catch you.’ This happens after Auberon’s death, in Ciri’s dream; as well as on every other occasion the Hunt appears on Ciri’s trail before she reaches Tor Zireael.

You belong to us.

It’s the collective that is being emphasised. In this way, Eredin shifts personal responsibility off his own shoulders to his co-conspirators, but he also draws authority from it. He acts on behalf of and in unison with a larger organism that is guided by ends higher than his own individual – indeed insignificant – ambitions. The elves, remember, are attuned to Nature and its holistic principles.

In the text, two evident forces act upon Eredin: desire for power and fear of failure. Desire for power binds him with Avallac’h and Auberon, and he defers to them as long as it serves their shared ends most efficiently. He works with the Plan not against it: his incidences of sabotage (e.g. mentioning Ciri’s ‘wild talent’) arise out of character flaws, for they quite simply do not make sense as intentional acts. Because from beginning to end, Eredin fears Ciri’s escape. Her imprisonment is a necessary evil to achieve the Alders’ ends. And Eredin, much more so than Avallac’h, is concerned with the harm Ciri can do rather than with the promise and hope she holds.

‘You must understand, Swallow,’ he rasped, ‘that you’re only delaying the inevitable. I can’t let you leave here.’

‘Why not? Auberon’s dead. And I’m nobody and mean nothing, after all. You told me so yourself.’

‘Well, it’s true.’ He raised his sword. ‘You mean nothing. You’re a tiny clothes moth that can be crushed in the fingers into shining dust, but which, perhaps, if it’s allowed, can cut out a hole in a precious fabric. You’re a grain of pepper, despicably small, but which when inadvertently chewed spoils the most exquisite food, forces one to spit it out, when one wanted to savour it. That is what you are. Nothing. An irritating nothing.’

The Witcher games got it right in this respect: fear motivates Eredin. Just as he motivates others with fear. In the absence of a supporting backstory, however, the games go a little too far with the ‘mad with fear’ angle. (The cut content does add some depth.) In Lady of the Lake, Eredin is by and large level-headed about their goals: why would he want to off Auberon if Lara’s father is their best genetic shot at back breeding (renewing and strengthening) the mutated Hen Ichaer? The only explanation that comes to mind is that Eredin might deem the laboratory a more foolproof and efficient means for achieving the elves’ aims, and does not understand why they are not making use of it; for Avallac’h and his laboratory are the canonical alternatives.

A clear cut regicide – not necessarily even a conniving pretender – Eredin Bréacc Glas is not. Ciri thinks so, but Ciri projects. Eredin is astonished once Ciri breaks the news on Auberon’s fate. Eredin doesn't have a false persona that gets stripped away.